Rally Blog

Mickey Mantle: A Tragic Prodigy

Blog >

Mickey Mantle: A Tragic Prodigy

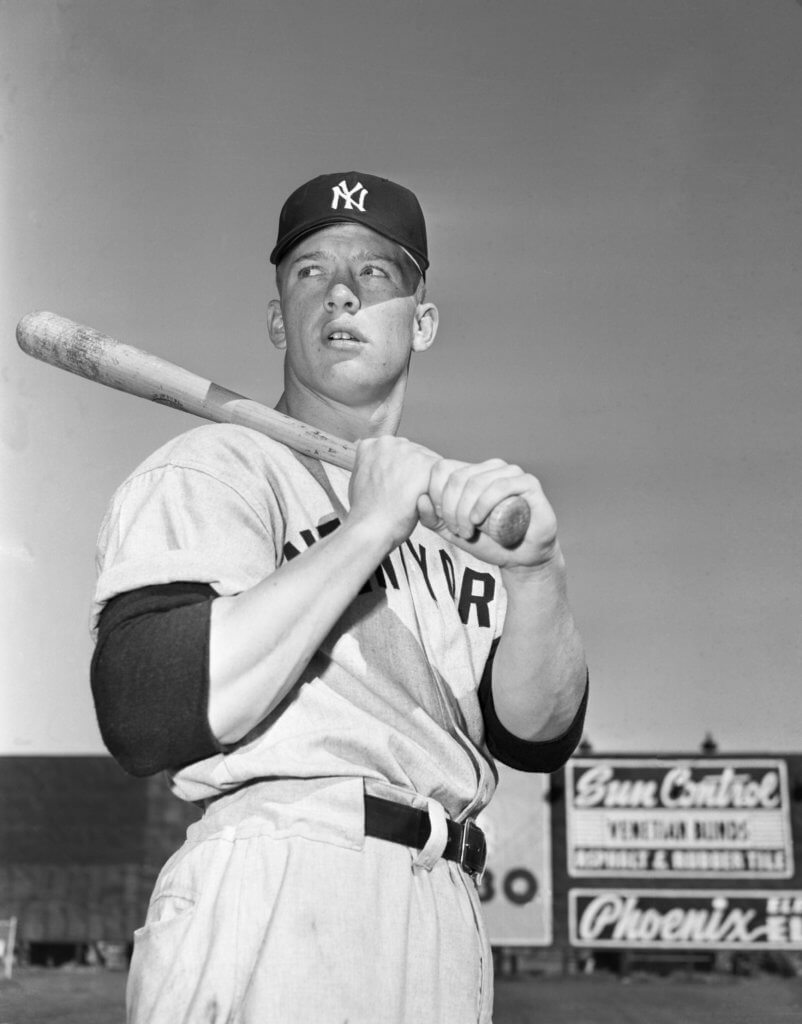

By the time Mickey Mantle arrived for Yankees spring training in 1951 at the age of 19, he had already become the stuff of legend. Scouts whispered stories of his time playing Class C ball in Joplin, where the muscle-bound teenager had launched home runs “that never came down… still aloft over southern Missouri.”

“Just wait till you see this kid… There’s never been anything like this kid. He has more speed than any slugger and more slug than any speedster… and nobody has ever had more of both of ’em together.”

Casey Stengel During Mantle’s First Spring Training

As if the media-pressure wasn’t enough, Mantle was saddled with the ultimate responsibility by Pete Sheehy, the Yankees long-time clubhouse attendant in charge of distributing uniforms, who had witnessed the sequential greatness of Babe Ruth (No. 3), Lou Gehrig (No. 4), and Joe DiMaggio (No. 5). Now he would entrust Mickey Mantle with No. 6.

Mantle struggled his rookie season, settling into a devastating hitting slump and finding himself back in the minors and thinking about quitting the game of baseball altogether.

Six weeks later he returned and pulled his act together, batting .284 for the remainder of the season. He would always bear a mark of his initial shortcomings, though, having his No. 6 stripped in favor of the far less glamorous No. 7.

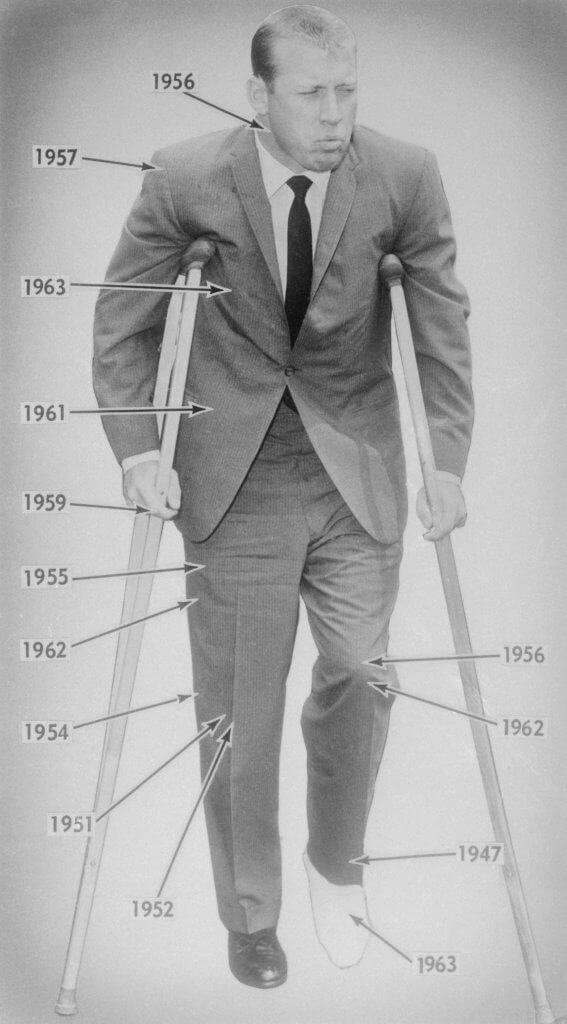

But at the end of that first season, he found himself in the outfield during the World Series. And, seconds later, he suffered a career-changing injury. After he was carried off the field in a stretcher with the sprained right knee that would sideline him the remainder during the ‘51 World Series, time stood still for Mickey, as well as his father Mutt, who was waiting in the dugout.

“I thought maybe he had fainted. You know, the tension of these things can do some funny things to you—and he’s only a kid.”

Yankees Coach Tommy Henrich

After staying the night in Mutt’s hotel room, the father and son would check in to Lenox Hill Hospital to survey the damage. Assisting Mickey as he struggled to walk, Mutt bore the physical weight of his protege’s injury. Mutt couldn’t muster the strength to support Mickey’s large frame, falling to the sidewalk.

Mutt had been battling Hodgkin’s lymphoma for months, never telling his son and he would die the following May. The loss of his father hit Mickey hard. After all, Mutt was the man who sculpted Mickey into the platonic ideal of a ballplayer that arrived in spring training the previous year. He had named him after Mickey Cochrane, who was the MLB’s best-hitting catcher at the time. The untimely deaths of Mickey’s grandfather, two uncles, and now his father, seeded the idea of a “Mantle Curse,” that would become a self-destructive life philosophy for the player.

A Feared Curse Made Personal

Growing up in the small town of Commerce, Oklahoma, both Mickey’s father and grandfather were hard working miners but always made time to hone Mickey’s skills. Most importantly, they trained him as a switch hitter from an early age, a regiment that was made far easier thanks to Mutt’s left-handed pitching and Mickey’s grandfather’s father’s right-handedness. It was the perfect recipe for producing the greatest switch-hitter in baseball history.

“The only thing I do left-handed is hit a baseball.”

Mantle

With Mutt’s death, his childhood hero may be gone, but Mickey’s career was just beginning — albeit to an inauspicious start. After the infamous 1951 World Series injury, it’s been said Mick never played another pain-free game for the rest of his career.

Casey Stengel once called him “the best one-legged player I ever saw play the game.”

The slew of injuries to follow not only deprived Mantle of his blazing speed — which once clocked him at 3.1 seconds from home plate to first, a mark which, if true, would make him the fastest player in history — but also helped to foment his alcoholism, which began after Mutt’s death and would continue for the rest of his life.

Of his fear of dying early, he once said: “I’ll never get a pension. I won’t live long enough.” And after years of drinking and carousing with Whitey Ford and Billy Martin as his chief running mates, he joked, “If I knew I was going to live this long, I’d have taken better care of myself.”

New York Times

Despite his 17 years of greatness as the face of the Yankees and becoming the de facto avatar for the All-American Boy in broader pop culture, Mantle’s hard-partying ways were a constant reality — one that he would only publicly regret towards the end of his life.

He’d reflect on the words of Stengel, who said he was going to be better than the great DiMaggio, and even Ruth. Then remember the hopes of his father, lamenting how he failed him. “It didn’t happen. I never fulfilled what my dad had wanted, and I should have…”

A Surprise Elder Statesman

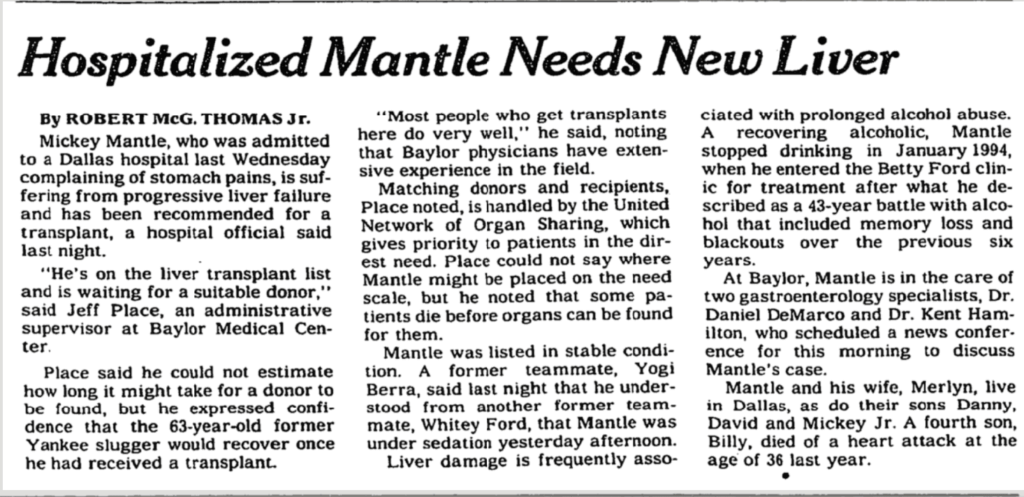

In a 1994 article in Sports Illustrated titled: “Time in a Bottle,” Mantle faced his addiction head on, describing the spiraling trend of his addiction, which led to the a morning routine he called the “’breakfast of champions’” — a big glass filled with a shot or more of brandy, some Kahlúa and cream.

“When I used to do card shows, guys would come up to me all the time, tears in their eyes, and they’d say, ‘Mickey Mantle. I’ve been waiting all my life to meet you.’ This one guy said to his little boy, ‘Son, that’s the greatest ballplayer that ever lived.’ And the little boy looked up and said, ‘Daddy, that’s an old man.’”

Mantle

His drinking had accelerated in the last couple decades of his life after the terminal diagnosis of his 19-year-old son Billy, who eventually died of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Yet another example of the Mantle curse.

In SI the piece, Mickey described seeking treatment at the Betty Ford Center. An admission of mammoth proportions from a man who was idolized by legions of masculine and presumably closed-off men.

I feel more important as Mickey Mantle now than I did when I was playing for the Yankees. I was told that I got more letters at Betty Ford than anybody else in its history, and 80% of them said things like, “You’re in the biggest game of your life, and we want to see you win again.” If I can stick with it, I’ll get their respect again, instead of being remembered as, “Well, there he is again, and he’s drunk.”

Mantle

Mickey’s sobriety came too late it seems, as he would die in August 1995 of cirrhosis of the liver among other alcohol-related causes. Just a month prior, in a press conference aimed at the nation’s children, Mickey delivered a final, devastating message.

“Don’t be like me. God gave me a body and the ability to play baseball. I had everything and I just …”

Mantle