Blog > Stories

Game Boy Glasnost

Blog > Stories

Game Boy Glasnost

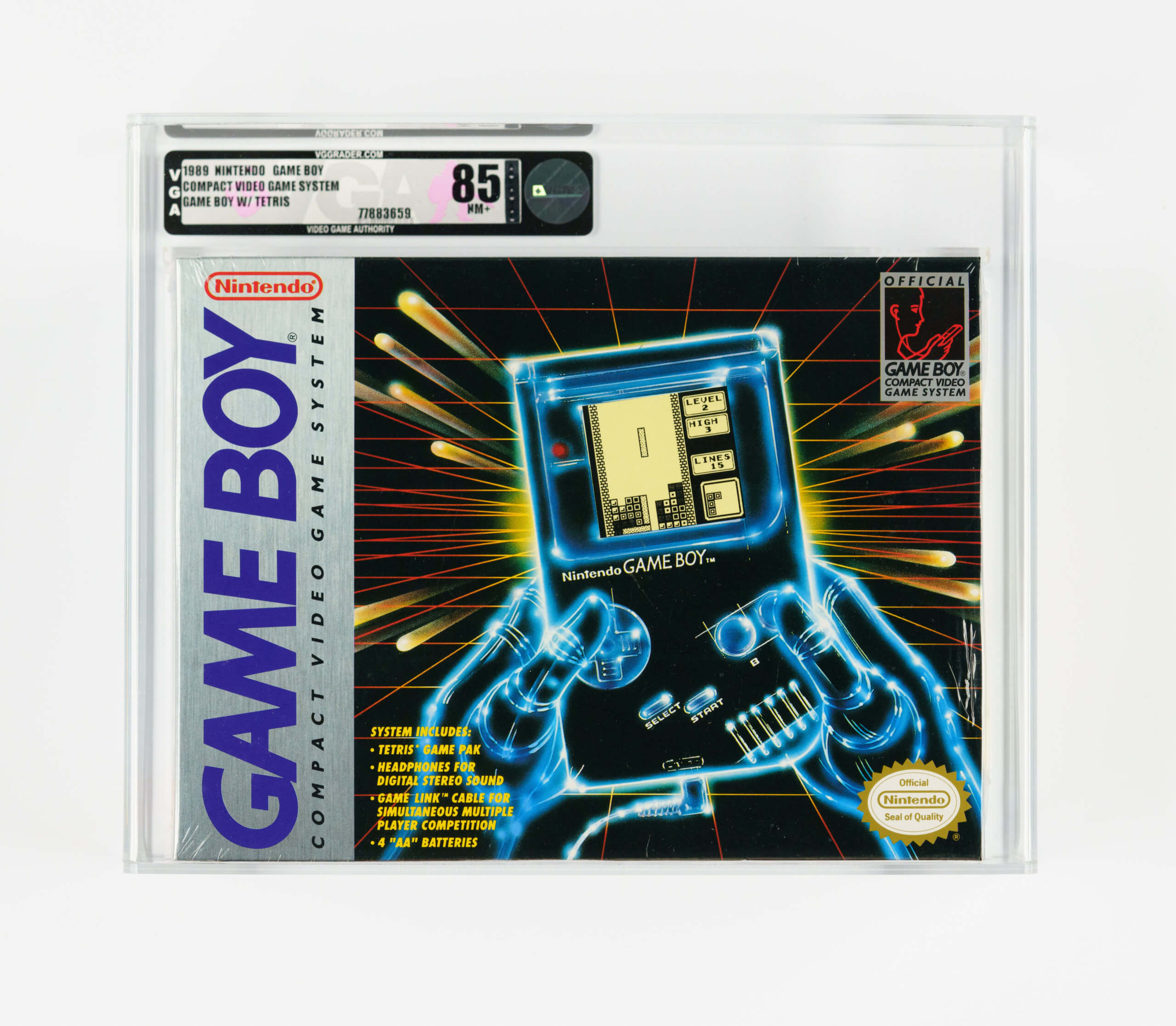

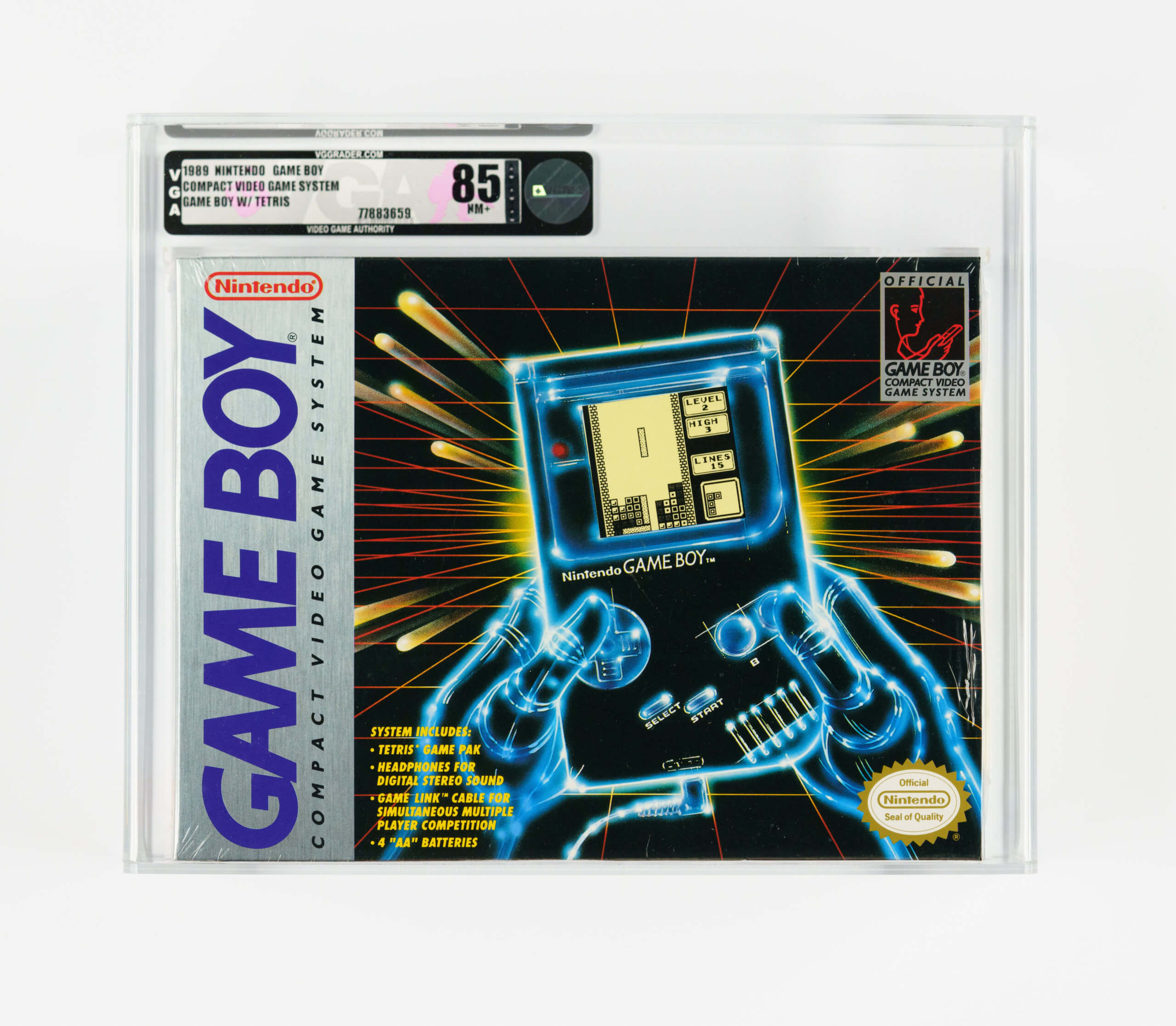

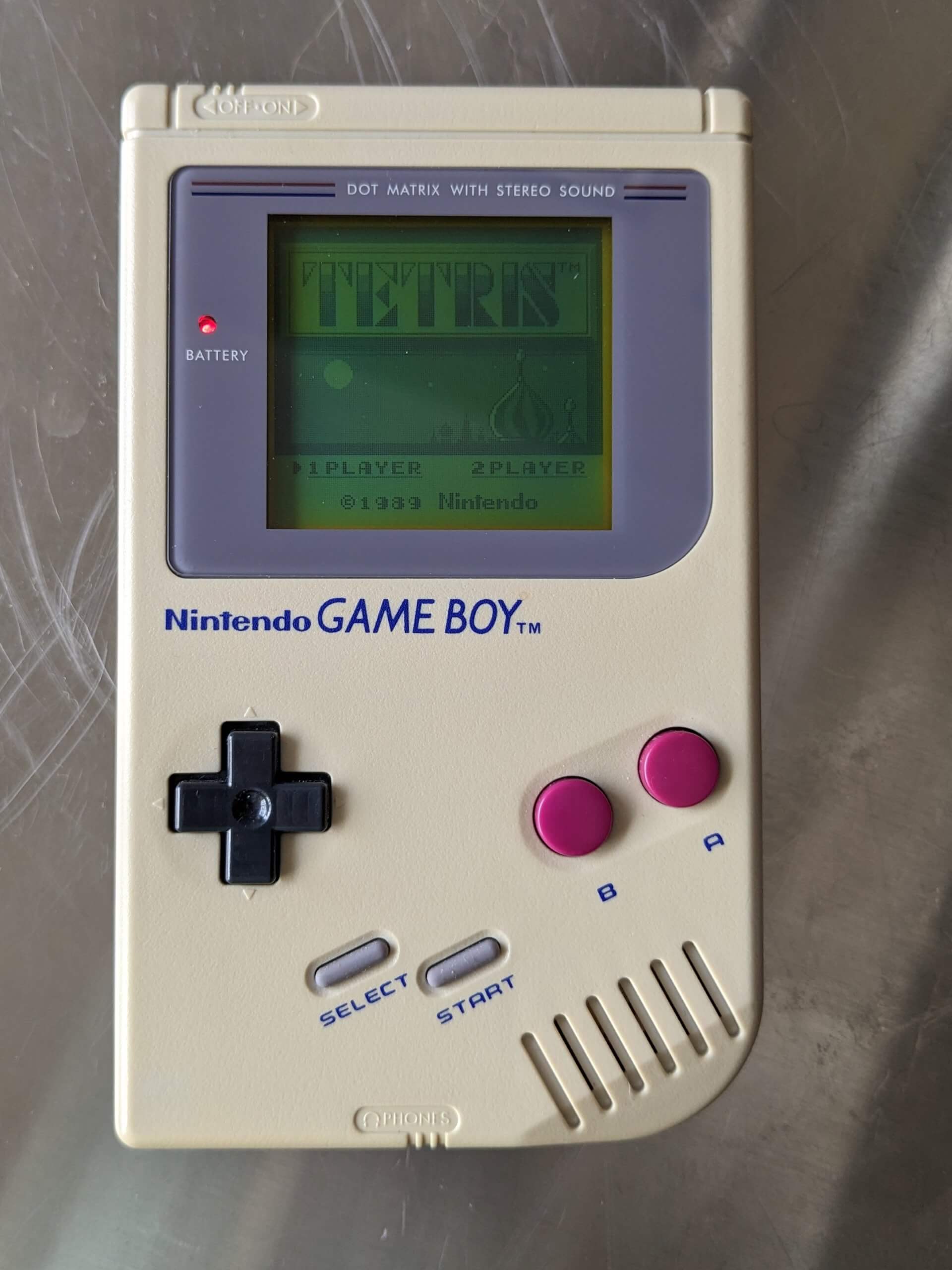

When the Soviet Union fell at basically the same time as Nintendo’s Game Boy was being released globally (1989), there was an unexpected overlap of two concepts powering towards international pop-culture supremacy – a newly open invitation to “exotic” Russian artistic history, and the realized dream of on-the-go gaming.

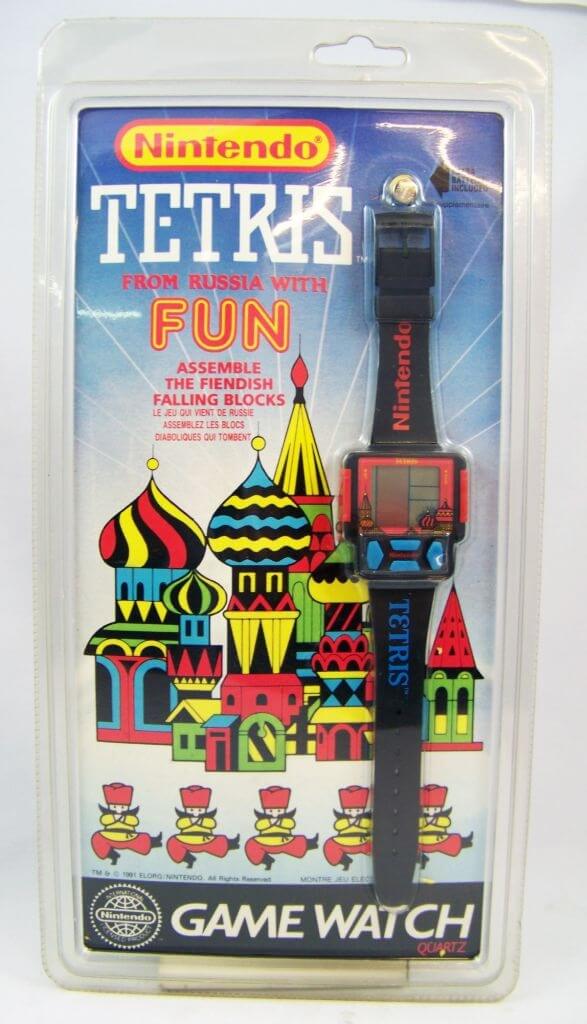

Both were summoned onto Tetris – the Game Boy’s killer app and one of the best-selling games of all time, and maybe the most-played title of all time. Original taglines before the portable release of the game labeled it, cheekily, as “From Russia With Fun.”

Drama From the Start

Tetris had been developed as a student project in the U.S.S.R., hitchhiked its way to (now) Eastern Europe, and was the focus of the wildest series of events that have ever graced the concept of “brand licensing.” (This story is the focus of an Apple+ movie with a trailer that’s like The Wizard meets Argo. We’re very excited for it). Making a great story shorter, Nintendo eventually got the handheld rights and planned to pack Tetris in with the launch consoles globally. The game was already successful as an arcade stand-up and home console release, along with a submarket of hundreds, maybe thousands, of computer knockoffs.

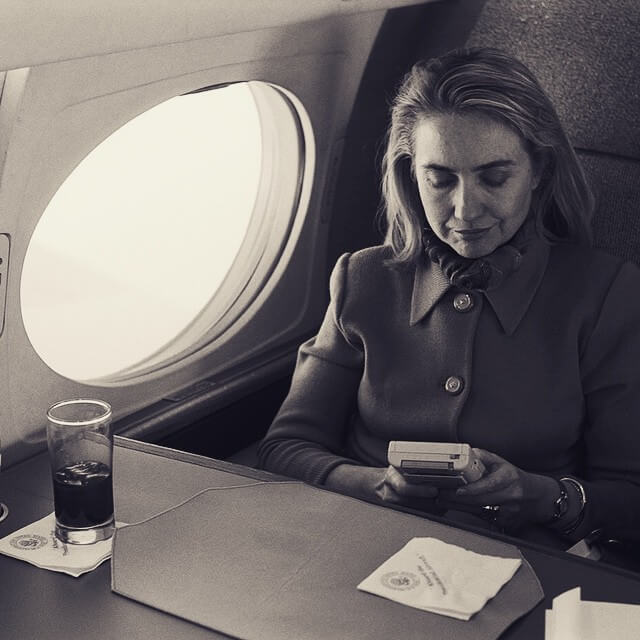

Puzzle video games were very (very!) common at the time, and many children’s first toys are freaking blocks, so how did this game become such a cultural touchstone? Why do we have the “Tetris Effect” and, with less than a few years since the end of the Cold War, was a game featuring a Kremlin-eque building on the loading screen embraced by kids, adults, and then First Lady, Hillary Clinton?

Publicly. Enthusiastically! Obsessively. Having to buy a second Game Boy to support a grandmother’s addition was a common story, and any families who managed to divvy up time between children probably should have won an international peace prize. It was a phenomenon, even with its beefy size, greenish-white and grey-esque-black screen (without a backlight), and allowance-destroying appetite for batteries.

Without getting too in depth on the specs of the Game Boy, it’s easy to say that it was less robust than PCs, arcade machines, and home consoles of its time. From a capabilities standpoint, its peers were older and simpler and games on those machines shared a lot of the Tetris ethos – easy to understand, simple scoring, minimal features or modes, super straightforward controls, and a built-in progression that would end your session. It is a formula that’s appealing to everyone who can manage the buttons and disregards age, social status, and whether or not they’re “real gamers.”

Iron Curtains Tie the Room Together

But more than those other entries, Tetris also has personality. Eventually, the pieces themselves would be characters, like in Puyo Puyo Tetris by Sega. But at the Game Boy launch, the extra je ne se quoi comes from very Russian cultural references. William Gibbons’ essay “Blip, Bloop, Bach? Some Uses of Classical Music on the Nintendo Entertainment System” muses out loud about the soundtrack and landscaped menu screens. “What cultural factors encouraged the game developers to exploit the game’s international origins? …After the tense atmosphere of the early 1980s, the changing social and economic policies of the USSR and the revolutions of 1989 were slowing [sic] altering American perceptions of Russia and its culture.” In summary, “Tetris plays into this alteration; rather than presenting Russian culture as universally negative, the game’s music, in-game visuals, and marketing all play into presenting Soviet culture as exotic yet positive.”

Tetris plays into this alteration…presenting Soviet culture as exotic yet positive.

William Gibbons

Nintendo and the other companies marketing Tetris weren’t going out on a limb here. The 1990 Goodwill Games in Seattle were accompanied by an art exhibit called “Between Spring and Summer” and centered on modern Russian artists whose work had been developed behind the Iron Curtain. The fall of the Soviet Union and the instability of many countries led by communist governments kind of merged together, pop culturally, and made thematic ties between the Chernobyl disaster and glasnost, among other references, summarized under a general “pro-democracy” banner. The Winds of Change were blowing around the Western world.

Russians, generally, and communists, regardless of nation, were everywhere in pop culture and American tastemakers couldn’t seem to settle on a narrative. In 1985’s Rocky IV, the main characters are consumed by an unsportsmanlike, unrepentant Russian fighter and we are all treated to Siberian training montages and a Christmas Day rematch in Moscow. Just one year later, in 1986’s Top Gun, the bad guys are implied to be Russian, but not really named as the clear opponent. The menace and reason for the Navy’s elite flight school is left as a secondary threat after Mavrick’s ego. TV shows had subplots where Russian ballet stars escape their handlers and defect to the west (based on true stories) and advanced placement students went on cultural exchange trips to the former Soviet Union (Head of the Class season three Mission to Moscow Parts One and Two, here’s to you). Communism was used in the news as an extreme foil to free democracies – the fall of the Berlin Wall on one hand and the Tiananmen Square massacre on the other.

Fun with Terror

Now back to “From Russia With Fun.” Americans were happily ambling down this wide boulevard of obsession, with nuclear terror on one side and charming novelty on the other, when the Game Boy Tetris bundle was released. And families everywhere chose the traditional folk music soundtrack and onion topped buildings to be a token of exciting cultural exchange, instead of the invasion of a hostile ideology. This isn’t anything new. As a society, we do this all the time and with similarly dubious litmus tests.

Ancient Egypt was the thing when the treasures from King Tut’s tomb were found and again when they set up shop in museums around the world from 1972 to 1981 as the first blockbuster touring exhibit, and gave us the threat of deadly curses foiled against the lush, “exotic,” and gold-plated pharaoh style. “The Amazon” was characterized as a crucial environmental resource (which it is) but also home to “savage tribes” who had never met modern man and might kill you with a blow dart?

Above all, the game was a success because of gameplay! But maybe it was a phenomenon because it was also left with a little bit of personality, even for a game about stacking blocks.

The Tetris and Game Boy story is totally bananas and this is the teeniest sliver of it! For more information, check out Tetris: The Games People Play and then go on a research rabbit hole through Tengen, the fall of the Soviet Socialist Republics, early American Nintendo management, and political discourse on 1980s presentation of communist ideals.

SOURCES AND ASSETS

1989 NINTENDO GAME BOY (SEALED WITH TETRIS PACK-IN)

Sources:

Brown, Box. Tetris: The Games People Play. First edition. New York: First Second, 2016.

Croizier, Ralph. “The Avant-Garde and the Democracy Movement: Reflections on Late Communism in the USSR and China.” Europe-Asia Studies 51, no. 3 (1999): 483–513. http://www.jstor.org/stable/153693.

William Gibbons. “Blip, Bloop, Bach? Some Uses of Classical Music on the Nintendo Entertainment System.” Music and the Moving Image 2, no. 1 (2009): 40–52. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/musimoviimag.2.1.0040.

Filipovic, Elena, Claire Bishop, and Boris Groys. “Between Spring And Summer, Soviet Conceptual Art in the Era of Late Communism.” Edited by Jane A. Sharp. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012.

Edwards, Phil. “The sad story of how Hillary Clinton got addicted to Game Boy.” Vox, April 20, 2015. https://www.vox.com/2015/4/20/8459219/hillary-clinton-gameboy.

BONUS CONTENT

Winds of Change podcast: https://crooked.com/podcast-series/wind-of-change/