Blog > Stories

Superman And Batman: How Surprising Sources Shaped The Characters We Know Today

Blog > Stories

Superman And Batman: How Surprising Sources Shaped The Characters We Know Today

Friends and Enemies

The Family He Chose

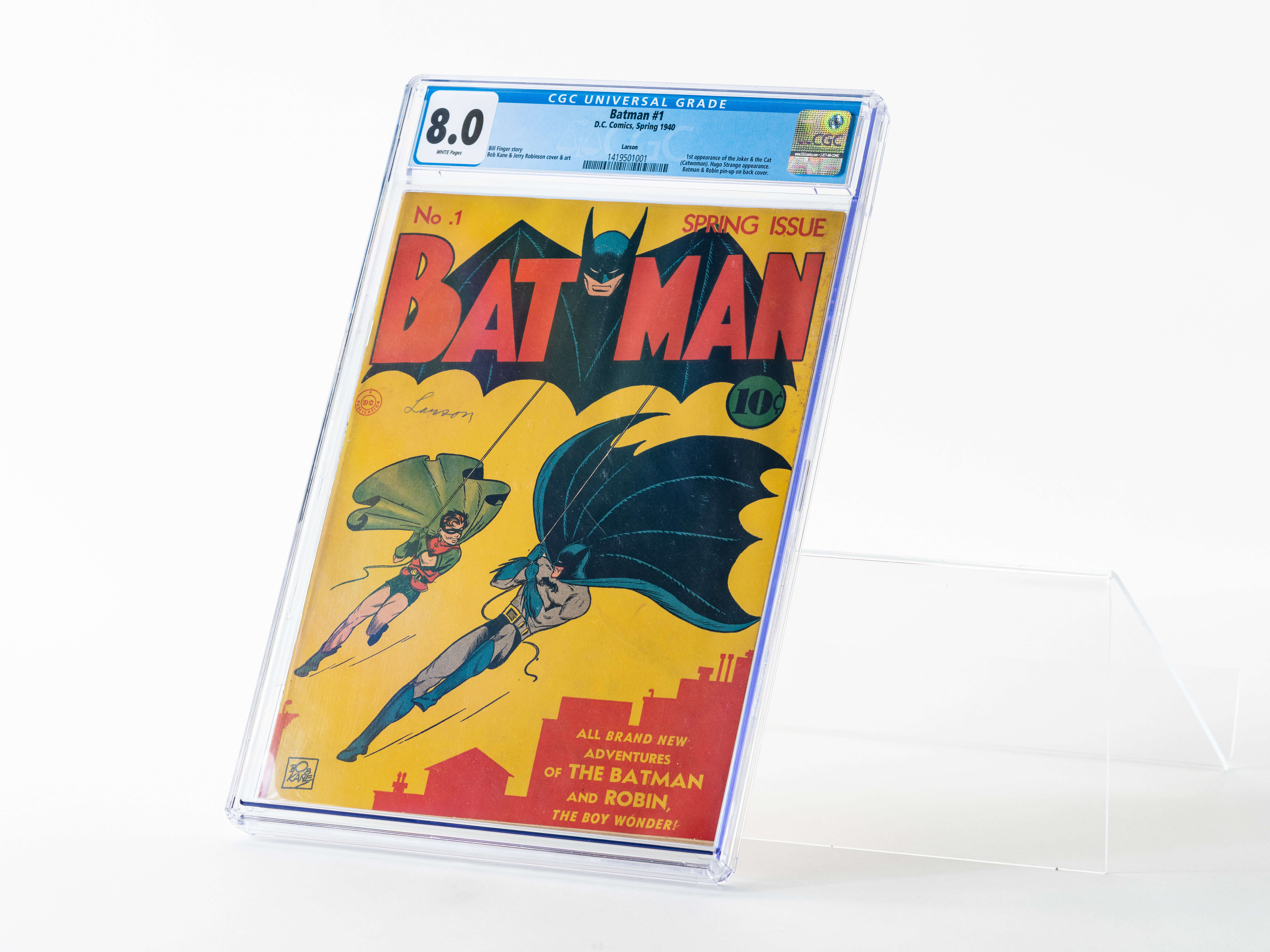

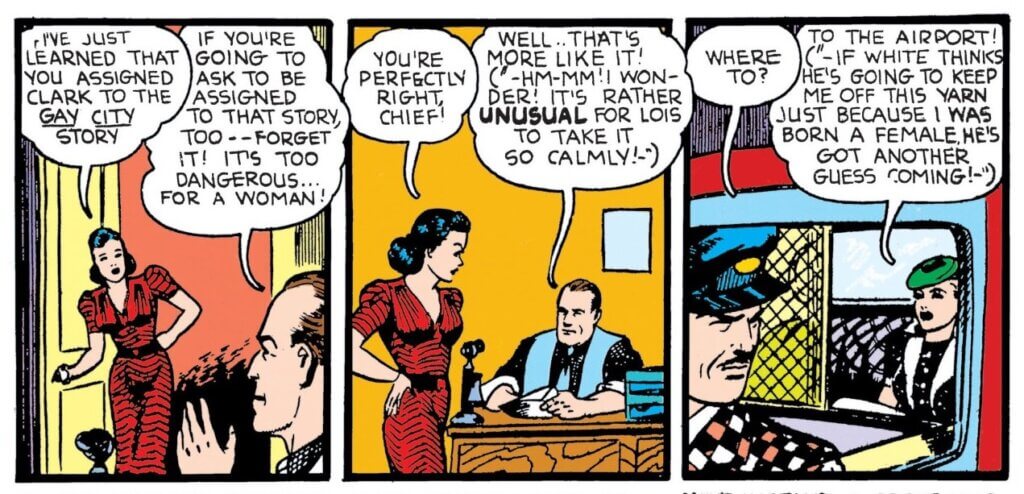

When you think of Clark Kent’s core posse, Lois Lane, Jimmy Olsen, and Perry White are the first to come to mind. Of these three, only Lois got her start in the comic book world.

Clark and Lois start out at The Daily Star in Action Comics #1 working under an unnamed “editor.” Eventually, he would pick up the name George Taylor. With no fanfare, the paper’s name changes to The Daily Planet in a November 1939 Superman newspaper strip. The new Superman radio show went with the strip’s Daily Planet name when Clark showed up to get a job there in the second episode on February 14, 1940. Curiously, the editor in the radio version was named Perry White instead of George Taylor.

The Superman newspaper strip and radio show gained in popularity with a more mainstream audience and the comic books eventually caved to these new names, adopting The Daily Planet in Action Comics #23 (April 1940) and Perry White in Superman #7 (November 1940). In both cases, readers were given no explanation – undoubtedly confusing those who were exclusively comic book readers at the time. It seems most readers just shrugged and flipped to the next page.

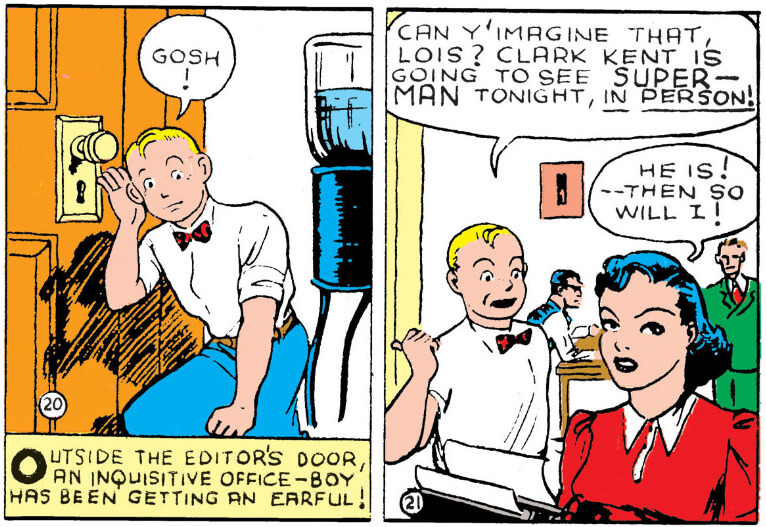

Superman’s pal Jimmy Olsen could technically have been the unnamed blonde “office-boy” that showed up from time to time starting with Action Comics #6 in November 1938. However, he didn’t have the name and look we know today until an episode of the Superman radio show.

“As our story opens today, Clark Kent is about to leave the Daily Planet building when he is hailed by young Jimmy Olsen, a red-headed, freckle-faced copy boy who works in the editorial department of the paper.”

The Adventures of Superman radio show (April 15, 1940)

Young Jimmy asks Clark for help in dealing with some gangsters demanding protection money from his mother for her candy store. You’d think Superman could stop this problem immediately, but writers manage to stretch this story into six episodes.

Olsen returned regularly after this and became a popular character on the show. The comic books officially included “Jimmy” in Superman #13 (November-December 1941), though he remained blonde for some reason.

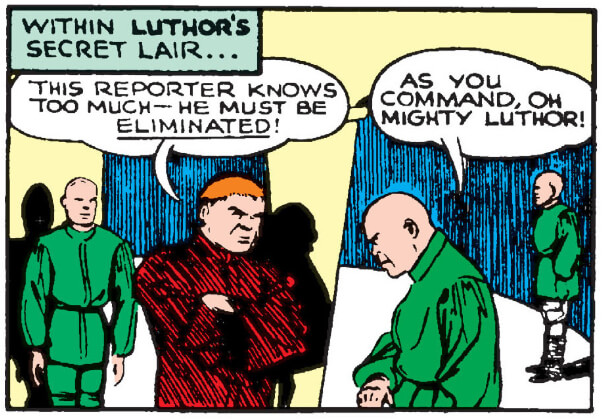

Speaking of hairstyles, Superman’s greatest nemesis, Luthor, debuted in Action Comics #23 (April 1940) with a shock of red hair (the “Lex” would come later). Throughout subsequent comics appearances, this look persisted.

It wasn’t until November 1940 that he first appeared bald in the daily Superman newspaper strip. Superman co-creator Joe Shuster ran a team of ghost artists to keep up with the ever-growing content demands while battling deteriorating vision. One young artist, Leo Nowak, drew Luthor bald during this series. The change uncontested, Nowak drew Luthor bald again in Superman #10 (May-June 1941) and the evil mastermind stayed that way from then on.

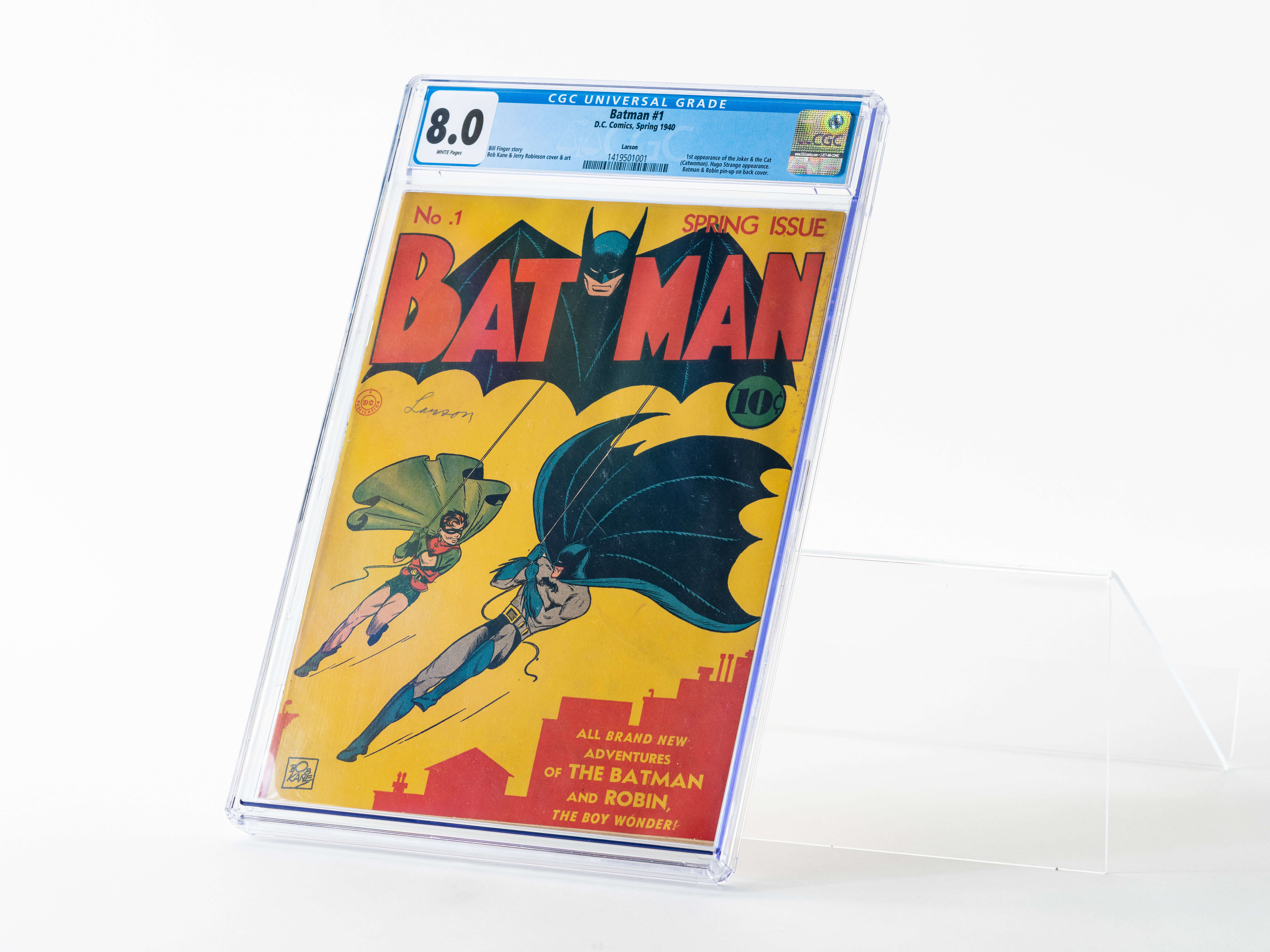

Batman’s Gotham Gang

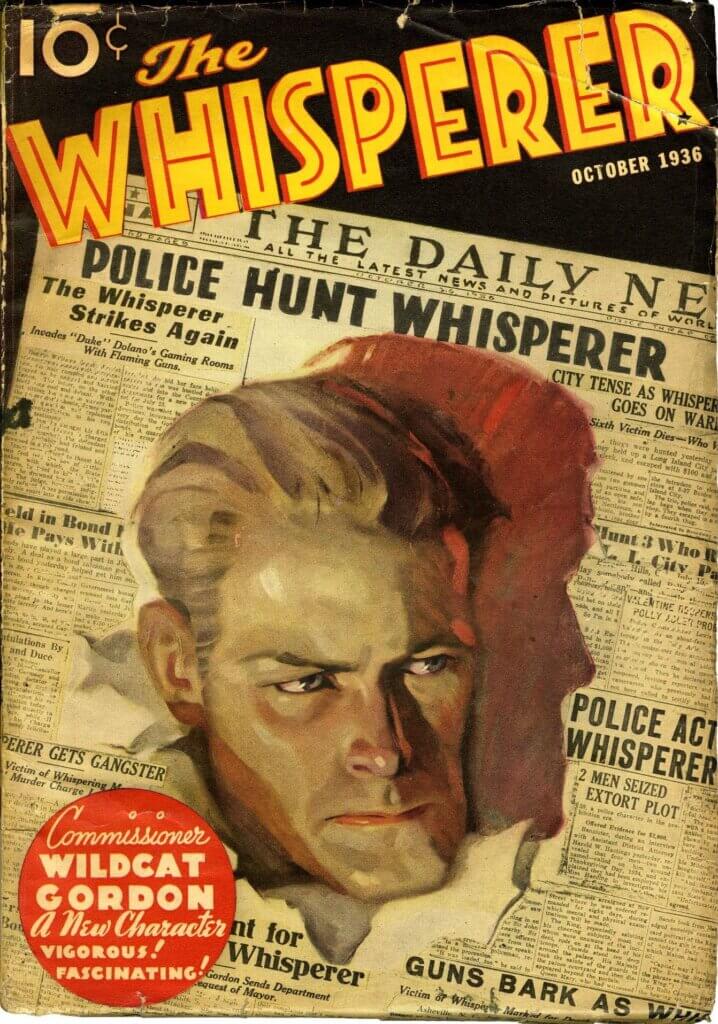

The only Batman character who hails back to the Dark Knight’s first appearance in 1939 is Commissioner Gordon. He would eventually get the full name James W. Gordon, which once again is borrowed from pulps. A magazine called The Whisperer debuted one James “Wildcat” Gordon in October 1936. He started as a police inspector who took the law into his own hands as The Whisperer, but by the end of that first story he was promoted to – you guessed it – commissioner. The Whisperer’s initial run lasted 14 issues, ending in December 1937.

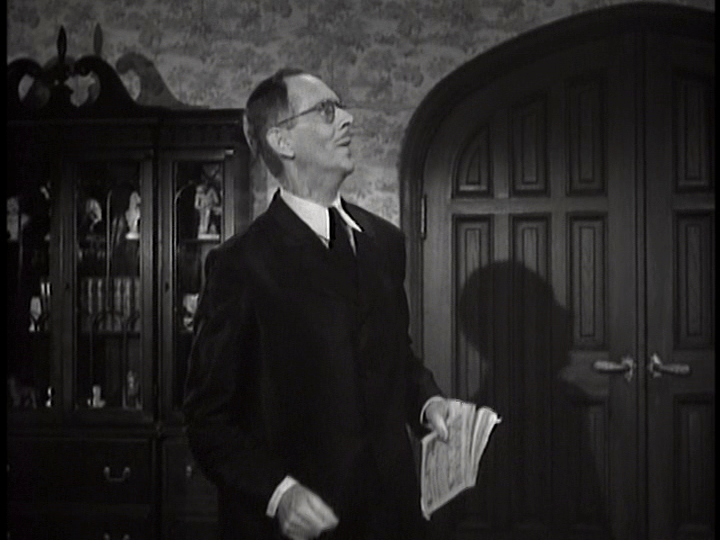

Loyal butler Alfred wouldn’t appear until Batman #16 (April 1943), but there is apparently evidence that he was created by the writers of the Batman live-action serial. DC then asked the comic writers to introduce Alfred so that the books paralleled what fans would see in theaters.

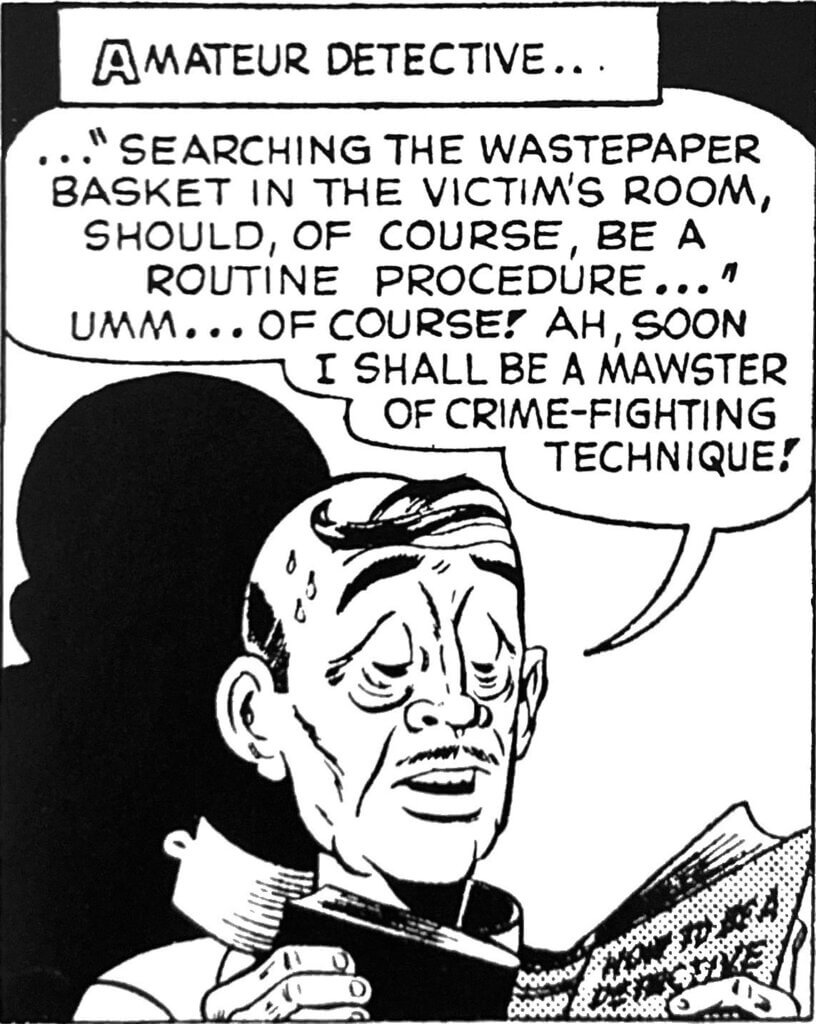

Not surprisingly for the time, there was no effort to standardize the character. The comics version of Alfred was portly and clean-shaven while the serial version, played by William Austin, was trim and wore a thin mustache. The first time he resembled Austin in print was in the daily Batman newspaper strip “Meet Alfred!,” which ran in 1943. He would lose the spare tire and grow a mustache in the main comic series all in the course of a single issue, Detective Comics #83 (January 1944). This was most assuredly not healthy, but at least the writers attempted to address Alfred’s change in appearance.

When Frederic Wertham’s book, Seduction of the Innocent, proclaimed comics’ supposed corruptive influence on children in the mid-50s, it upended the entire industry and resulted in the Comics Code Authority censorship board. One of the more notable of Wertham’s accusations was that Batman and Robin were in a gay relationship. To offset these charges, DC introduced Batwoman in 1956, followed by the original Batgirl, Betty Kane, in 1961.

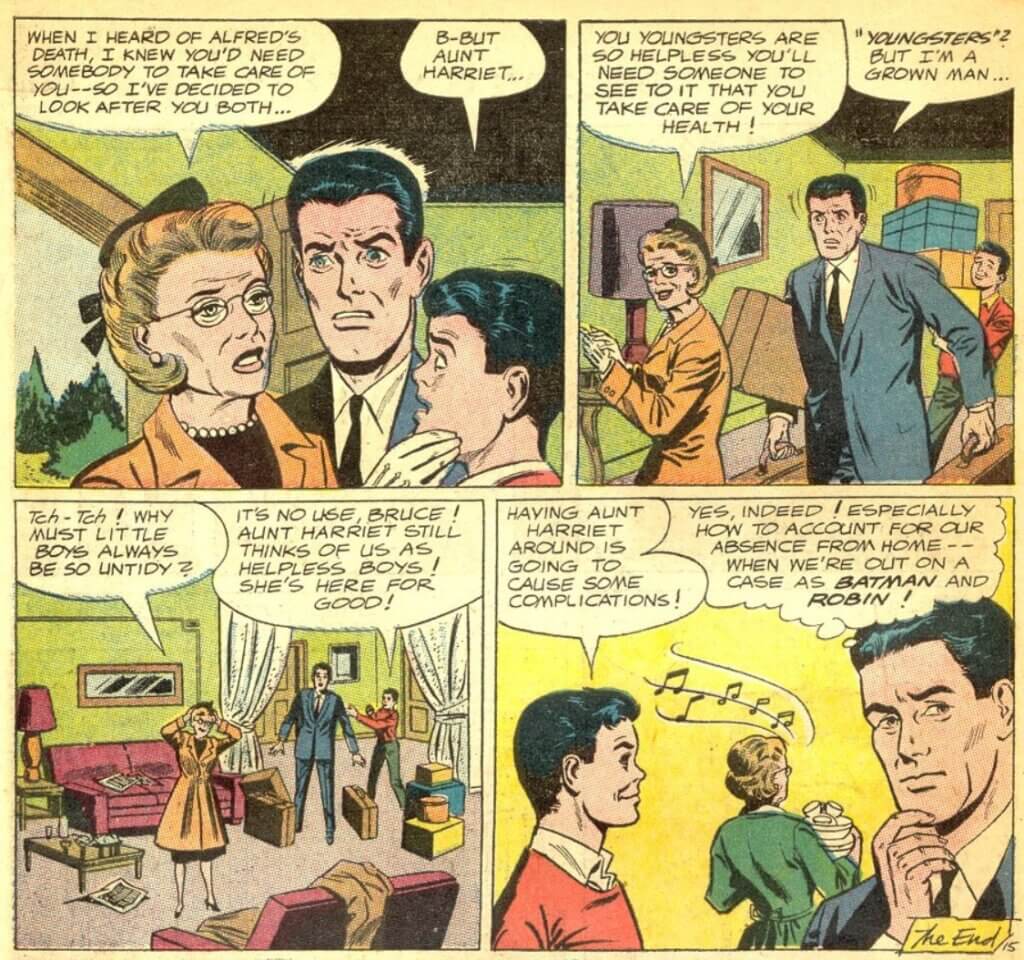

Even that wasn’t enough. DC decided to reduce the testosterone in the manor even further by smashing Alfred with a boulder in Detective Comics #328 (June 1964) and replacing him with Robin’s Aunt Harriet.

Fortunately, the creators of the eventual hit Batman TV show let DC know they were planning on using Alfred as a regular character. Once again, another medium forced DC’s hand to bring Alfred in line. The Batman show starring Adam West debuted on January 12, 1966 and was a huge sensation. By that fall, a resurrected Alfred was revealed as The Outsider, a villain intent on murdering Batman and Robin [Detective Comics #356 (October 1966)]. Though he quickly resumed his normal butlering duties after Batman punched him into a “regeneration machine.”

The show would go on to influence other parts of the Batman canon as well, mostly revamping pre-existing characters.

“When the ratings slipped on the TV show, they wanted a female interest. I don’t remember the exact details, but I was asked to create a Batgirl. I called Carmine [Infantino] in, and he drew the costume and did the cover. I worked out the story and called it ‘The Million Dollar Debut of Batgirl.’”

Batman editor Julius Schwartz in Batman: The Complete History

This new Barbara Gordon version of Batgirl would have much more staying power than Betty Kane’s. She debuted in Detective Comics #359 in January 1967 and later on the show in the season three premiere “Enter Batgirl, Exit Penguin” on September 14, 1967. While the show ended after that season, Barbara Gordon remains a key character in the comics and beyond.

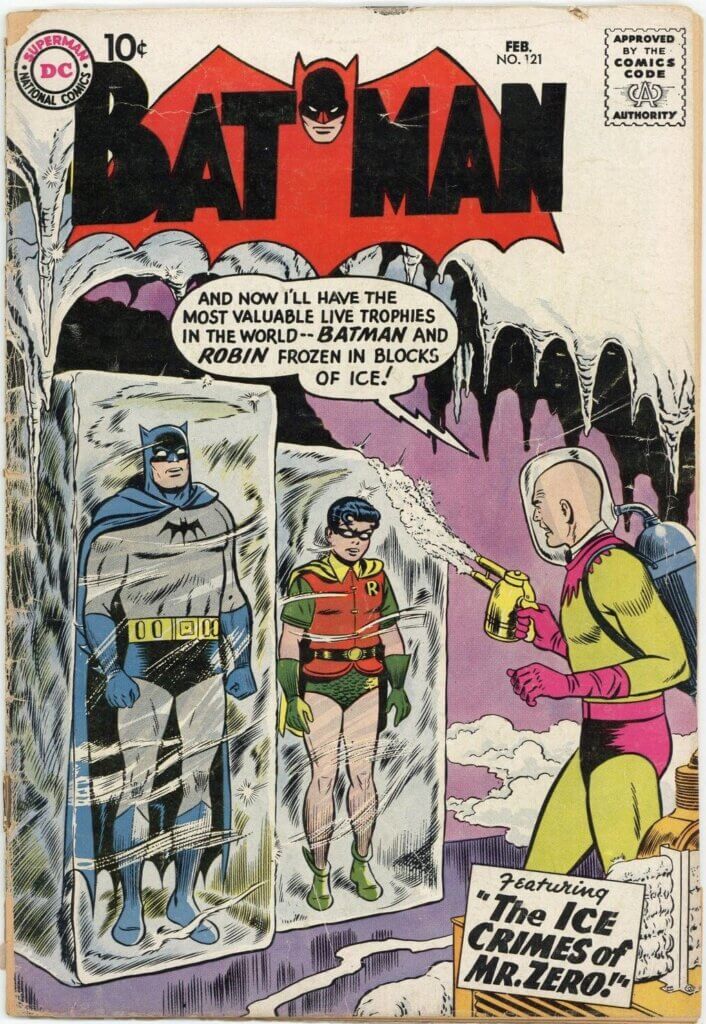

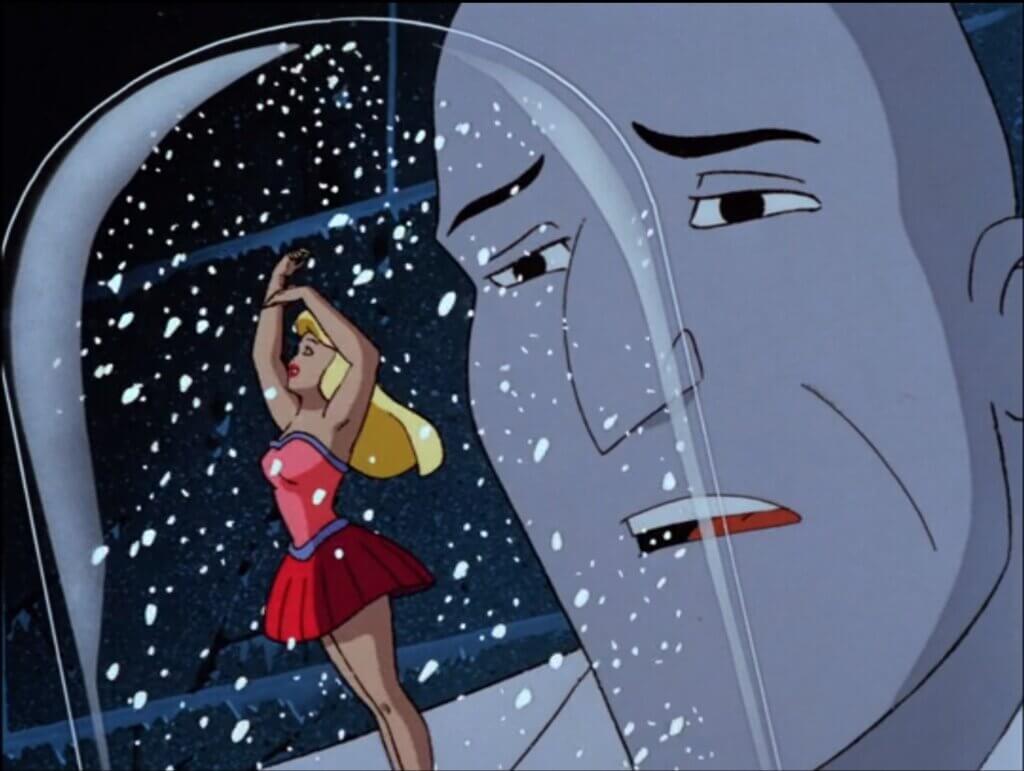

Mr. Freeze’s name came from the ‘60s TV show as well. Before the showrunners tweaked the villain’s name, he was called Mr. Zero in his comic debut [Batman #121 (February 1959)]. This wouldn’t be the last time a TV show would upgrade Mr. Freeze either. In the widely respected Batman: The Animated Series, Mr. Freeze would be given a new origin that was so impactful that it was officially adopted across the comics and beyond.

“Heart of Ice” (September 7, 1992) gave him the name Victor Fries and established that he cryogenically froze his dying wife, Nora, while searching for a cure to her illness. The only reason he turned to a life of crime was to fund his research and facilities (and get revenge on a heartless industrialist). It’s so much better than some scientist who got a cold chemical splashed on him in a lab accident.

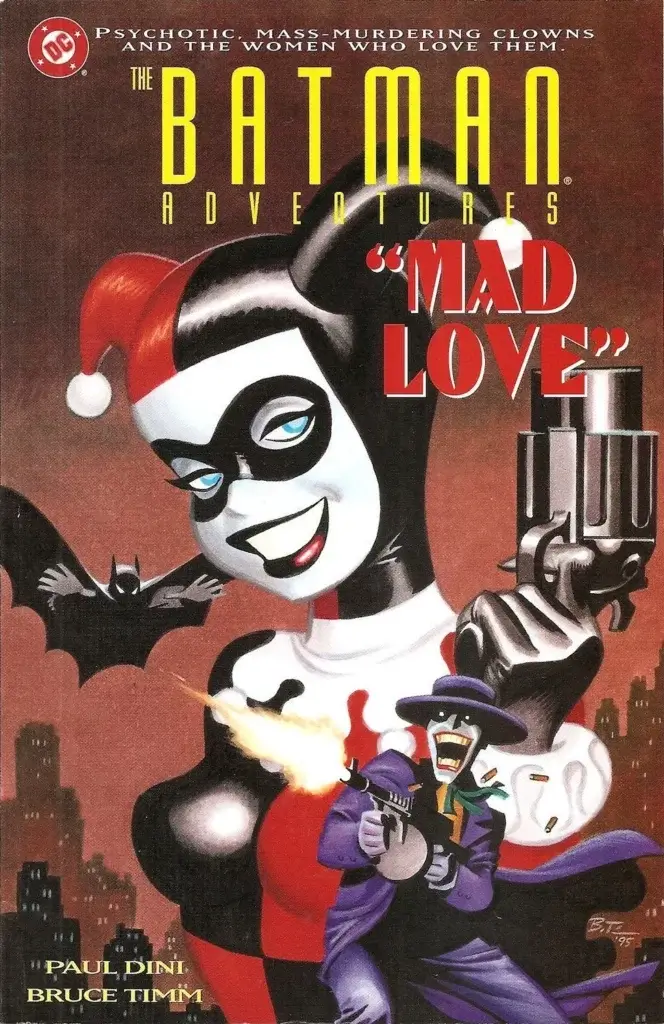

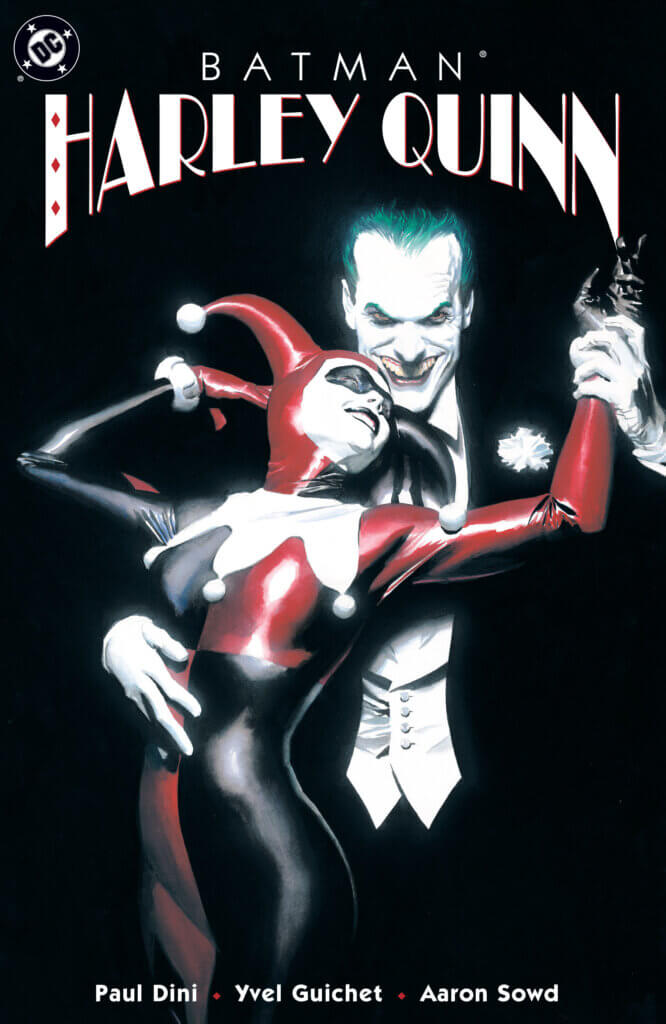

Unquestionably, the biggest impact Batman: The Animated Series had on the main canon was the introduction of villain Harley Quinn. Debuting in “Joker’s Favor” (September 11, 1992), Quinn immediately stood out as a character to watch. One year later she debuted in B:TAS comic spinoff The Batman Adventures #12. Then in February 1994, fans learned about her origin in a one-shot comic called The Batman Adventures: Mad Love made by the show’s Paul Dini and Bruce Timm. Mad Love would go on to win Eisner and Harvey Awards, but it wasn’t adapted back into the show that Quinn came from until January 1999 in the revamped New Batman Adventures. Quinn finally became part of the official Batman comics canon later that year in Batman: Harley Quinn #1 with an iconic Alex Ross-painted cover.