Blog > Stories

How to Talk About Pokémon at Dinner Parties

Blog > Stories

How to Talk About Pokémon at Dinner Parties

Realistic Made Up Creatures

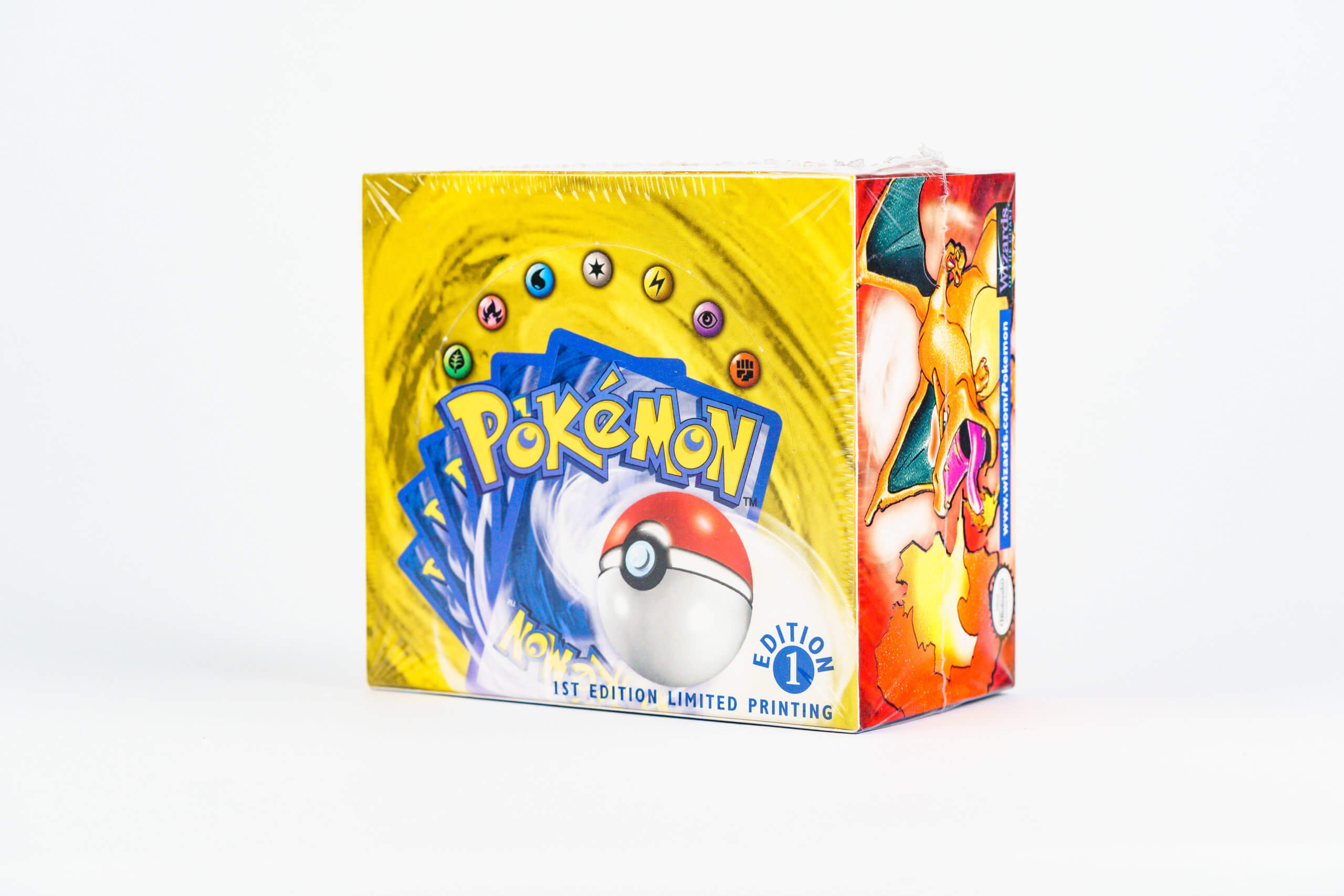

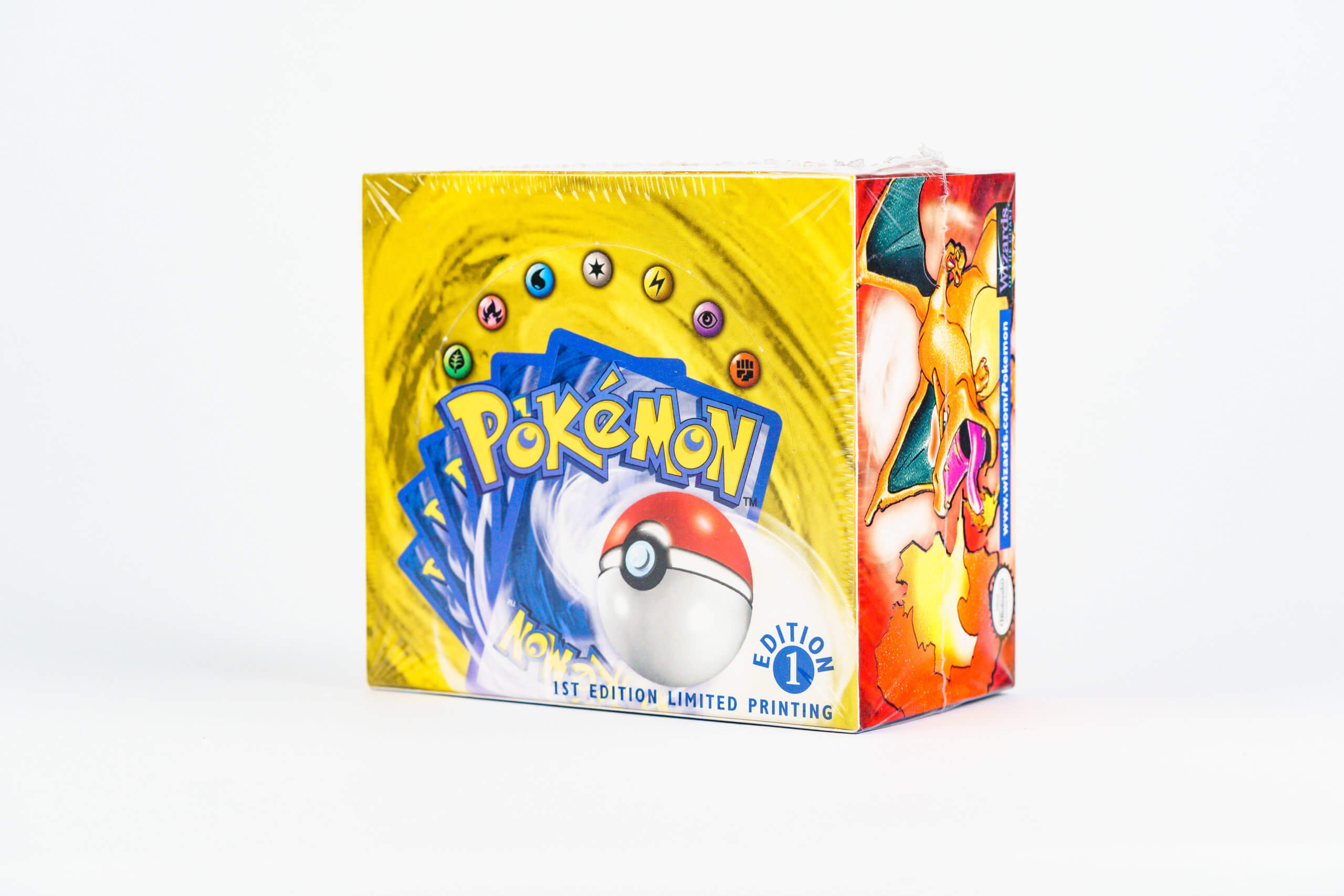

And now we can talk about what’s actually on those cards. In hindsight, the presentation of Pokémon themselves is obviously right. No notes! But, transitioning the content from the portable game that had lots of graphical limitations to printed cards wasn’t a direct line.

Pokémon Company President and CEO (who started on the TCG on day one), Tsunekazu Ishihara, said, “I was [initially] of the opinion that if the game mechanics in a TCG were interesting, then that’s all that mattered… If I were to take this to the extreme, I had the argumentative point of view that the illustrations on the cards themselves were unnecessary.” An early Charmander card changed his mind, though, by showing personality and behavior; an ah-ha moment where collectibility’s capitalism and artistic merit transitioned from two separate ideas into one shared powerhouse concept. This observation became an immediate obligation for the series, and has been admirably stuck to while still having a ton of style and presentation variation.

A couple of traits are 100% consistent, even across the thousands of cards (as of July 2022, Dexerto estimates just over 13,000). One, the Pokémon shown are individuals, not a definitive documentation of an entire species. The idea that individuals within a species are different is crucial, and allows for the divergent art styles and behaviors shown over time.

Two! Illustrations should connote the “charm” of the Pokémon. This was a concept that many illustrators brought up in Pokémon Trading Card Game – Illustration Collection and supports the original creator’s (Satoshi Tajiri) boyhood bug obsession, a pastime that was nurtured by seeing beyond the buggy creepiness that put off others.

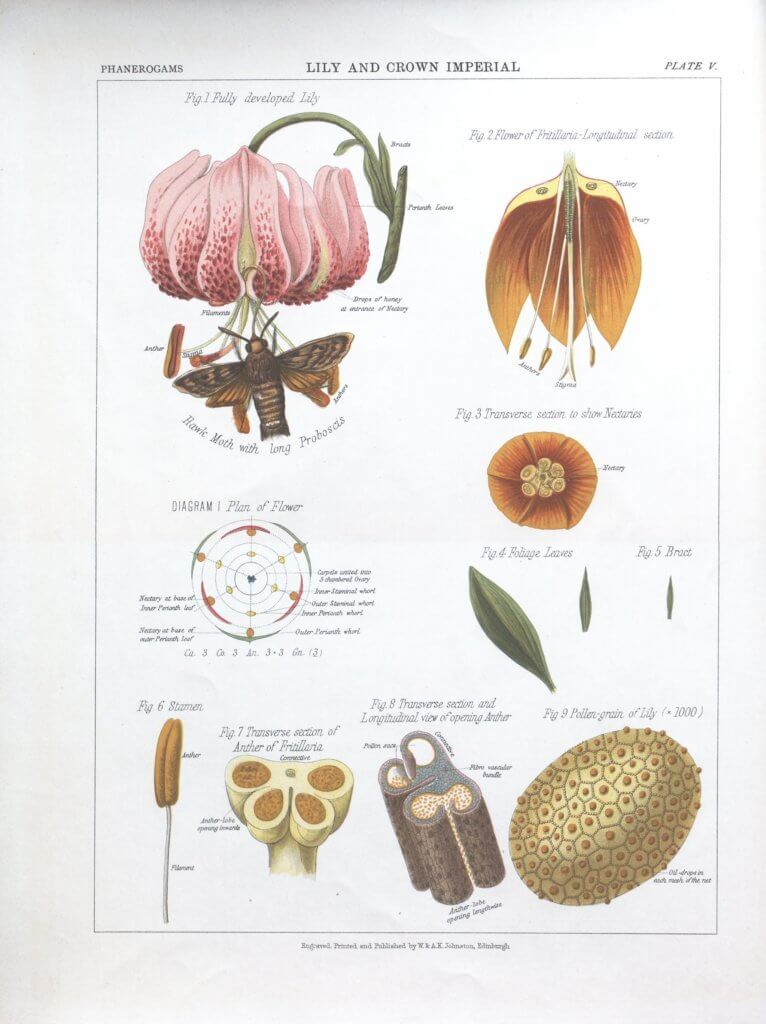

And lastly, the idea that these illustrations can (and should!) highlight a moment in the individual’s day or life. It isn’t an anatomy diagram or detailed identification manual. Illustrator Mitsuhiro Arita says, “…[55] there was some discussion that it might be better to draw just the characters without backgrounds to evoke a sense of ownership of the Pokémon, but, in the end, I proceeded with art that included backgrounds to emphasize the existence of Pokémon.” Illustrator after illustrator has mentioned that they wanted to present the Pokémon as if they really exist by including flora, other critters, and behaviors that reinforced the essential nature of the creature.

Origins of the Species Documentation

The card images have a clear inspiration and we bring, you guessed it, Victorian women back into the discussion. The era’s forming middle class needed obsessions, interests, and hobbies to match the priorities of intellectualism and consumerism that looser pocketbooks and the advent of middle-class steamship travel could provide. And here enters the concept of amateur intellectualism: League of Extraordinary Gentlemen-style explorers and cartographers, classicists fabricating/resurrecting the concept of the Olympics (first modern games were in 1896), world’s fairs, inventors (including a crazy race to formalize the technology behind photography), and fads like the Fern Craze of the 1840s-1860s.

While men quickly commandeered the “important” sciences, women and children were left to their own interests and devices when it came to botany and similar low-danger observations of the natural world.

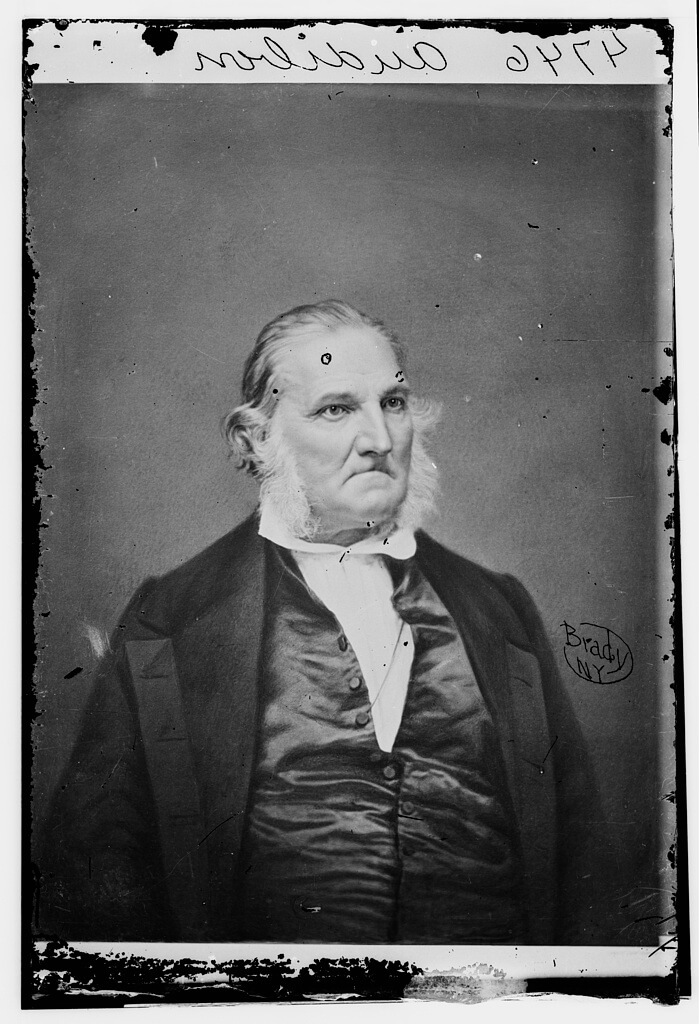

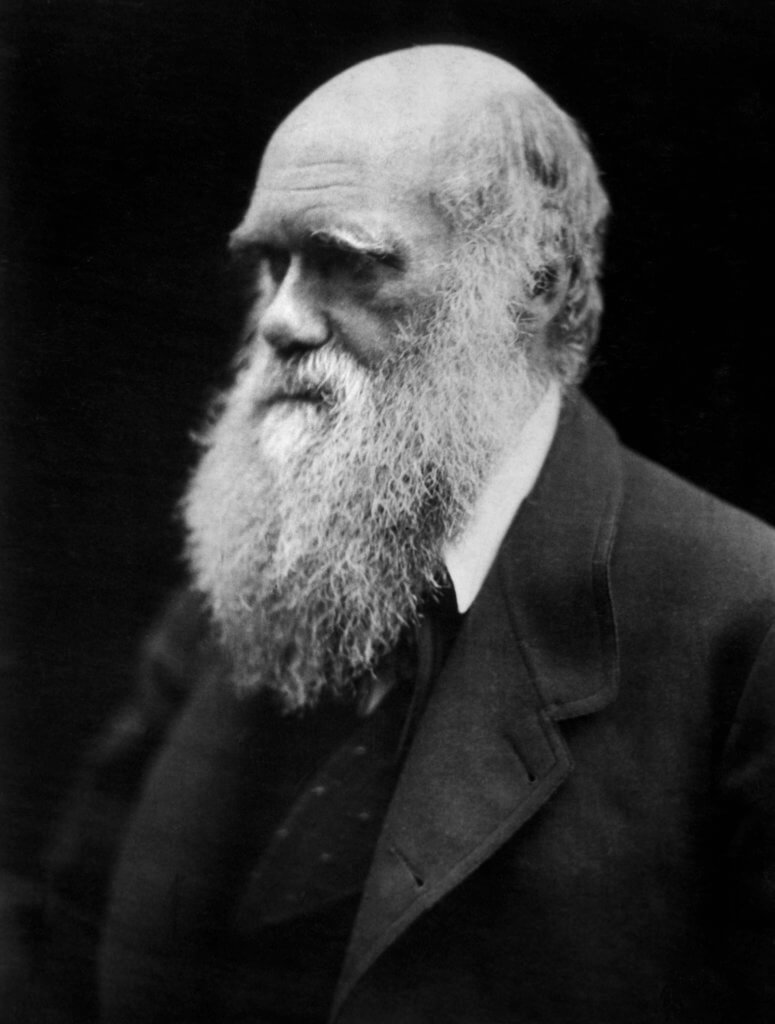

And so, if you asked lots of people to think about illustrations of nature and the kind of layouts where there are a few plants at different stages of blooming and birds with their eggs, babies, and male and female standard patterning; many would talk about John James Audubon (1785-1851) and Charles Darwin (1809-1882) and the like. But Audubon wasn’t nearly the first or even terribly honest with his observations and Darwin, by his own assertion, couldn’t draw (publishers sent artists out after his manuscripts were done to generate paintings on the selected topics).

Maria Sibylla Merian

Who we should be talking about is scientific artists like pioneer Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717), and Marianne North (1830-1890). Each are described as scientists first on their Google profiles, thank our robot overlords, and their innovations in observation, documentation, and aesthetic revolutionized both the art and science of their obsessions.

In the New York Times, Gettysburg College biologist Kay Etheridge and Merian researcher says, “She was a scientist on the level with a lot of people we spend a lot of time talking about… She didn’t do as much to change biology as Darwin, but she was significant.” And, she died nearly 70 years before Darwin was even born, having already traveled to South America and generating work that dispelled commonly-held beliefs that bugs sprung from mud as fully-formed adults.

She was the first to bring insects and their habitats into shared compositions. And the first to document a tarantula eating a hummingbird, which was initially mocked as impossible and is now confirmed as both true and very metal.

“It remains a splendid, lasting memorial of a remarkable woman, one whose ability and industry would certainly have gained her high appreciation at any later period but whose enterprise, originality, determination and courage stand out especially against her 17th-century background.”

William T. Stern about Merian

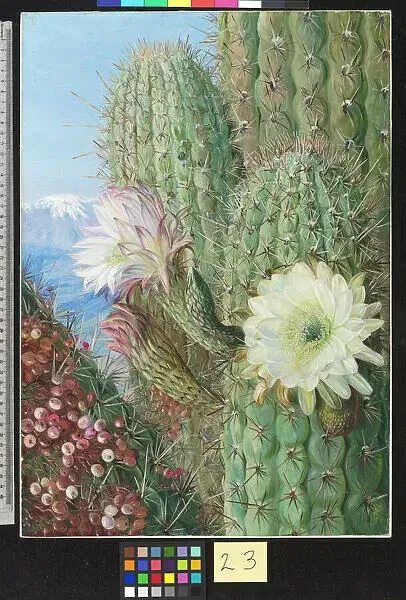

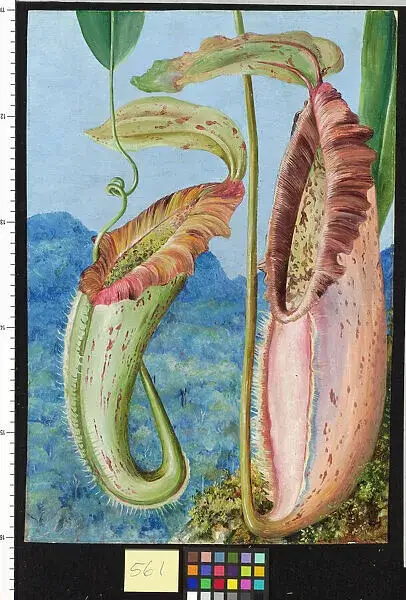

Marianne North

Marianne North was a Victorian woman who traveled the world alone (!) and discovered plants that were new to the burgeoning botanical sciences. Her oil paintings showed flora in the context of their surroundings and the records she kept documented location, habitat, and uses. The Kew Gardens in England (who house many of her paintings) point out that, “…years before the invention of colour photography, her paintings were a vibrant snapshot of faraway places that many people in Europe had never seen before.” Her bold and unladylike panache for exploration along with admirable documentary rigor is credited with the discovery of previously undocumented plants and other specialists in her field, like Darwin and botanical artist Katherin Saunders, were frequent contacts.

And all, every last one of them, are clear inspirations for the settings we see in so many Pokémon cards today.