Blog > Uncategorized

Mickey Mantle: From Oklahoma to Cooperstown

Blog > Uncategorized

Mickey Mantle: From Oklahoma to Cooperstown

An American Icon

“If Mickey Mantle hadn’t lived, he would have been invented.”

– Broadcaster Mel Allen

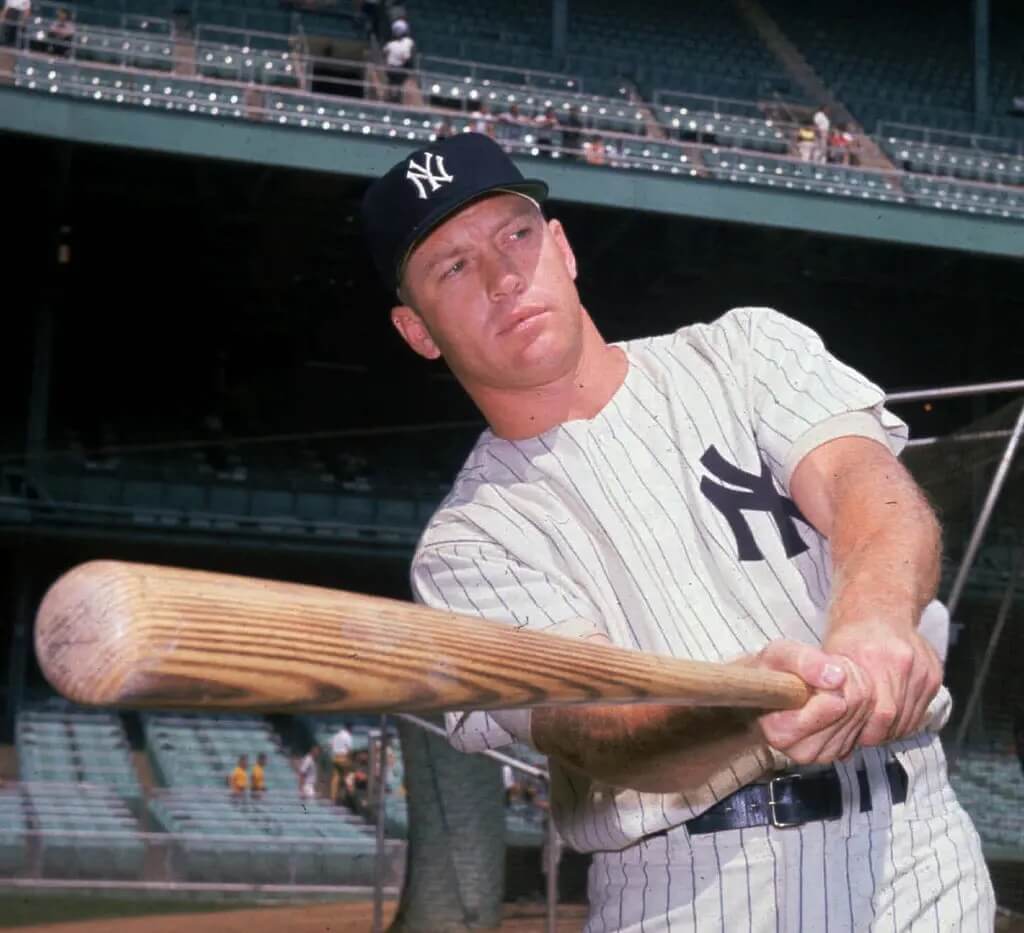

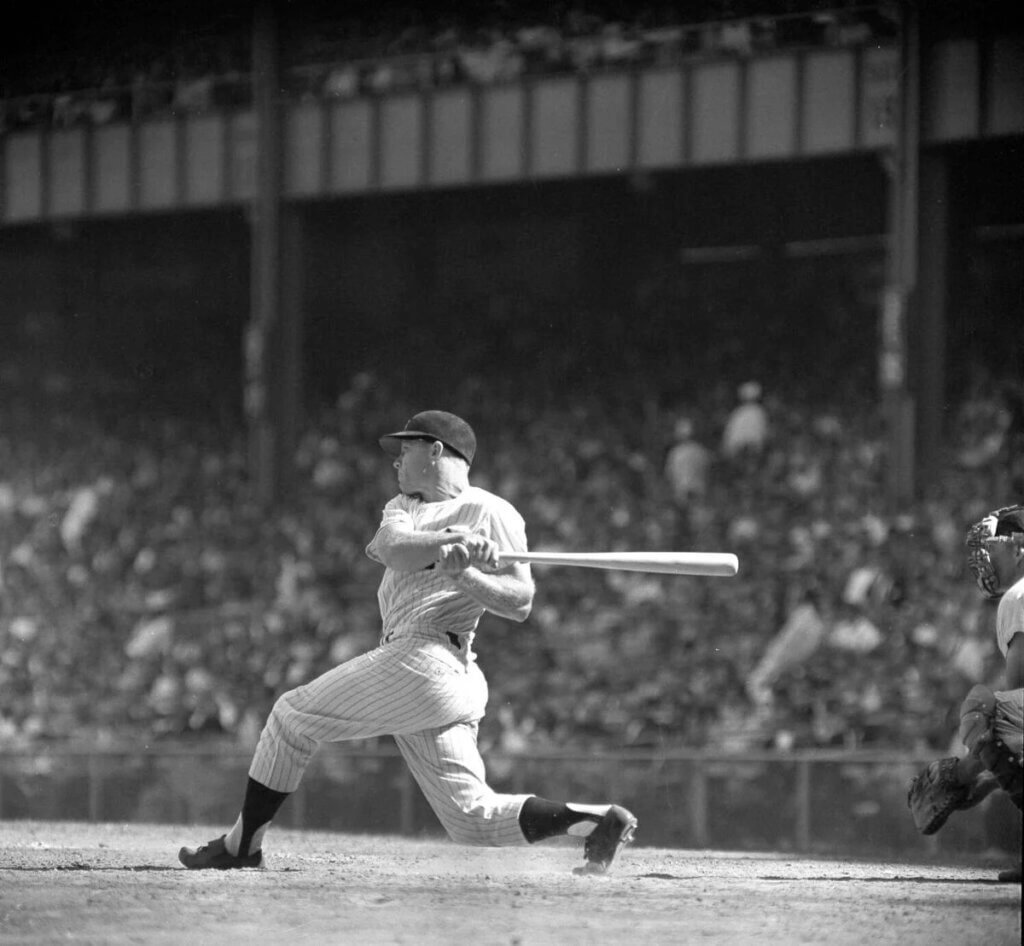

He ran faster than Rickey Henderson, hit the ball further than Barry Bonds, and hit more World Series homers than Babe Ruth… all the while switch-hitting with more success than any human to ever hold a baseball bat. He was built like the platonic ideal of a baseball player. But none of that explains the legend of Mickey Mantle.

In a game so beholden by labels — players are defined by their positions, play style (power hitter, defensive specialist, knuckleballer, etc.), statistics, and countless more attributes used by teams and fans alike to quantify an athlete — any ball player who defies classification is a subject of intrigue.

When it comes to evaluating Mickey Mantle, any attempt to place him in an archetype is a fool’s errand. While je ne sais quoi is used far too often and applied far too liberally, there’s no other way to describe Mantle for those who didn’t live through his career. Translating to “a quality you cannot describe,” it’s generally used in the positive sense, a way to explain a special sauce from an unknown source. While there’s no record of Mantle ever speaking French, there’s no doubting he embodied this expression to a tee.

As any contemporaneous reports and long-faded memories will attest, he possessed something beyond exceptional talent. The vocabulary to report on the exploits of Mantle literally didn’t exist… after he hit a 565-foot blast out of Griffith Stadium in Washington, D.C in 1953, the term “tape-measure home run” was invented. This doesn’t even take into account the three times he hit the facade at Yankee Stadium (rumors remain to this day that he hit just as many out of the ballpark in batting practice).

The Hall of Famer exuded the kind of self-certainty, myth-making, and fabled reputation that spanned far beyond the center field grass in the Bronx.

If ever there were an appropriate time to use the phrase je ne sais quoi, it’s in the fruitless attempt to describe The Mick in the language of his peers. There’s plenty of qualities that made Mantle into a star, but it’s the added level of his cultural heroism that forces one to acknowledge there’s just no possibility of evaluating Mantle on tangible merits.

He just had it.

Call it je ne sais quoi, call it charisma — it’s all the same inscrutable quality that elevated a top ten baseball player in history into an icon of Americana and realization of a dream during an era in desperate need of one.

Mantle’s 1951 debut couldn’t have been timed more perfectly. The war was over, the cultural upheaval of the following decades was beginning to take root, and sports journalists for magazines like Sports Illustrated, Sport, The Sporting News, Baseball Digest, and Time were entering into an age of influence, popularity, and significance never seen before.

A representation of a hopeful future who happened to look like a cookie cutter All American Boy from Oklahoma, Mantle served his role as a receptacle for the lofty aspirations of the day. As the sports journalism industry formalized itself as a staple of the MLB ecosystem, particularly in New York, there was hardly a place one could look to avoid glancing Mantle’s boyish grin in a photo in an interview, commercial, or simply verbal recounts of his feats.

The sports writers were not secretly biased toward Mantle.

Much to the contrary…

They kept no such secrecy. They were unabashedly romantic over him.

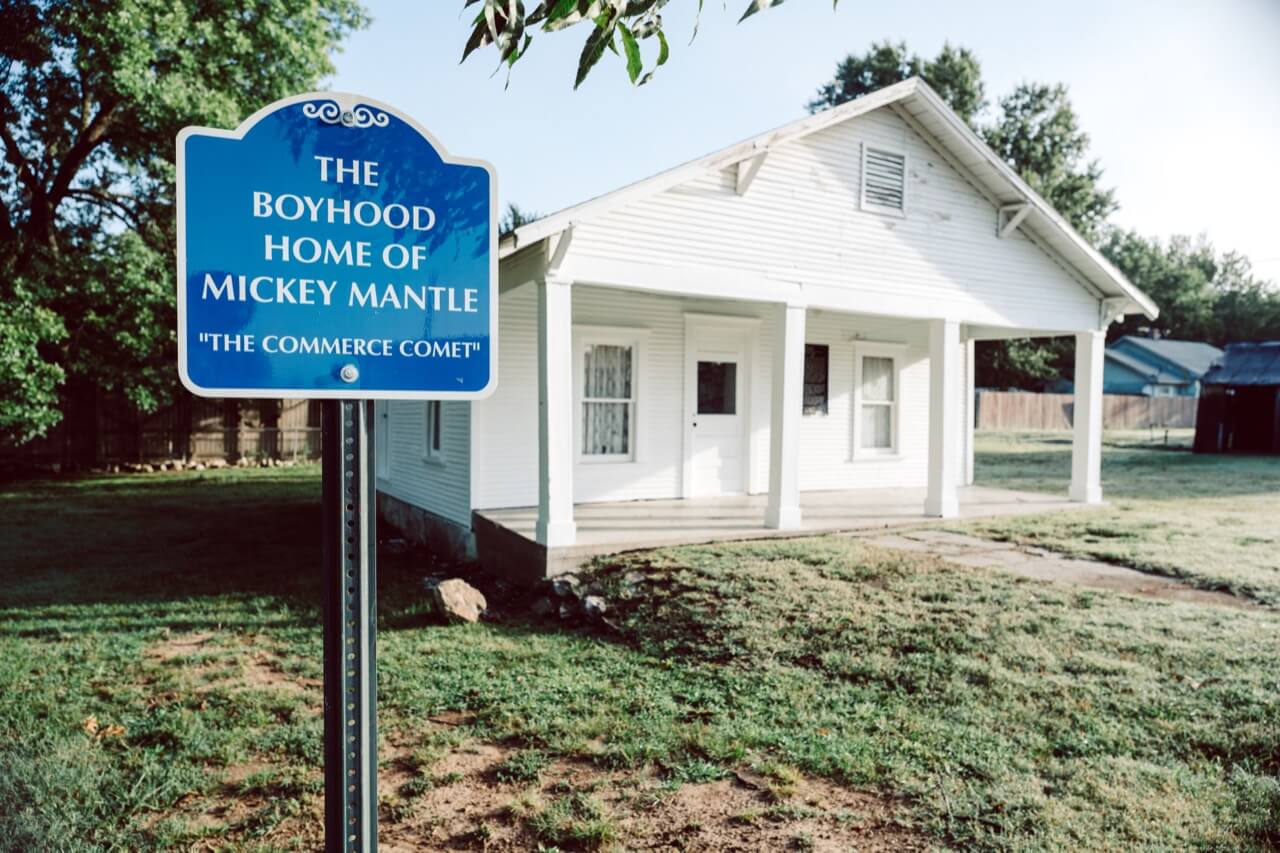

As Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist David Halberstam explained: “Most mythology is manufactured in New York about American virtues; thus the mythologists are from New York, but the mythologized are preferably from Commerce, Oklahoma.”

Halberstam’s diagnosis of Mantle’s Paul Bunyan-like stature is attributed to the eager nature of New York media to find someone to carry the flame of American values — not the kind from Manhattan, but the glorified sensibilities one can only find out west.

This review of Mantle’s myth-making is not simply a tactic to impress upon any non-believers the allure of Mantle, but more importantly, to illuminate the context in which he found himself a happy piece of clay primed for molding by reporters.

As the American Heritage Magazine writes:

“Since 1920 sportswriters had helped create New York baseball legends. They transformed George Herman Ruth, a loud, boorish man, into the Babe, a jovial idol who loved children, candy, and soda pop as much as he did hitting home runs. They turned a distant, laconic DiMaggio into the incomparable Yankee Clipper, a reserved, classy paragon of excellence. They made Lou Gehrig, the reclusive son of German immigrants, into “the Pride of the Yankees,” a sentimental favorite who battled a debilitating and ultimately terminal disease with unmatched and unwavering courage.”

This was mid-20th century New York, a place where first place was an expectation and any other city was considered inferior. Bruce Catton illuminated the environment of the time, writing “New York made the pace; it led the way, and everybody else had to follow and like it.”

While it may not have required too much coaxing to recruit fans to root for the athletic deity named Mantle, the Yankees hometown was more than up to the challenge of establishing Mantle as the next big thing.