Blog > Stories

Music Theory and Vintage Sound Chips: The Different Versions of Zelda’s Iconic Music

Blog > Stories

Music Theory and Vintage Sound Chips: The Different Versions of Zelda’s Iconic Music

NES Launches Without Zelda

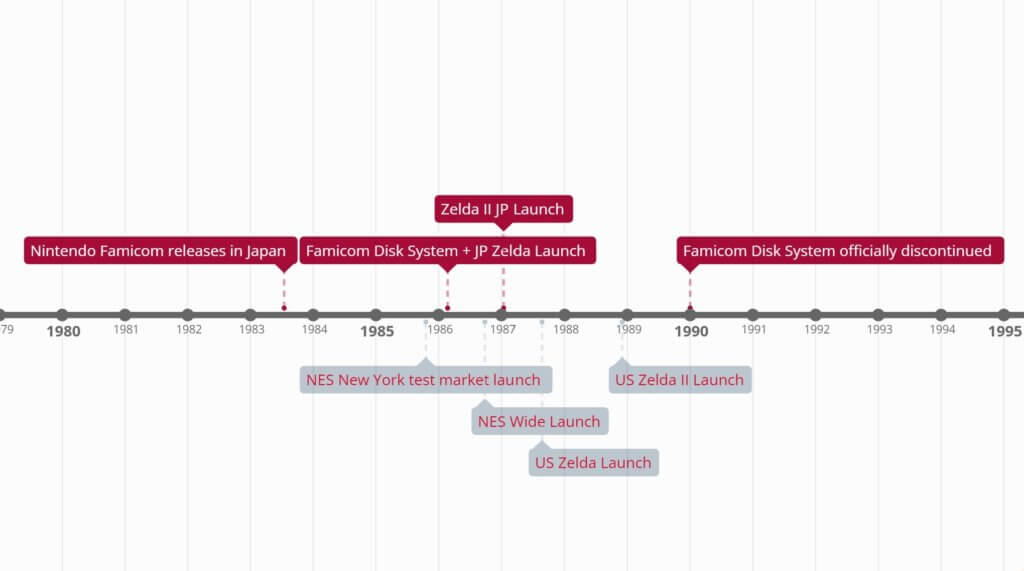

The NES first appeared in New York City as part of a test run on October 18, 1985, over two years after the Famicom’s debut in Japan. By this point in Japan, Nintendo felt technological and market pressure to keep up with newer consoles that had debuted since the Famicom’s launch and they offered the Famicom Disk System add-on to unlock further technological capabilities.

The FDS debuted in Japan on February 21, 1986 with killer app The Legend of Zelda showing what it could do. On September 27, 1986, the NES released to a national audience in the United States. Most western fans had little to no idea that they were getting older tech repackaged from a red and white top-loading system to a boxy, gray front-loading console.

An America-Tailored Release

Nintendo smartly populated the western launch with Super Mario Bros. and a variety of genre titles like sports (Golf, Baseball), lightgun shooters (Duck Hunt, Hogan’s Alley), fighting (Kung Fu), and arcade titles (Ice Climber, Wrecking Crew).

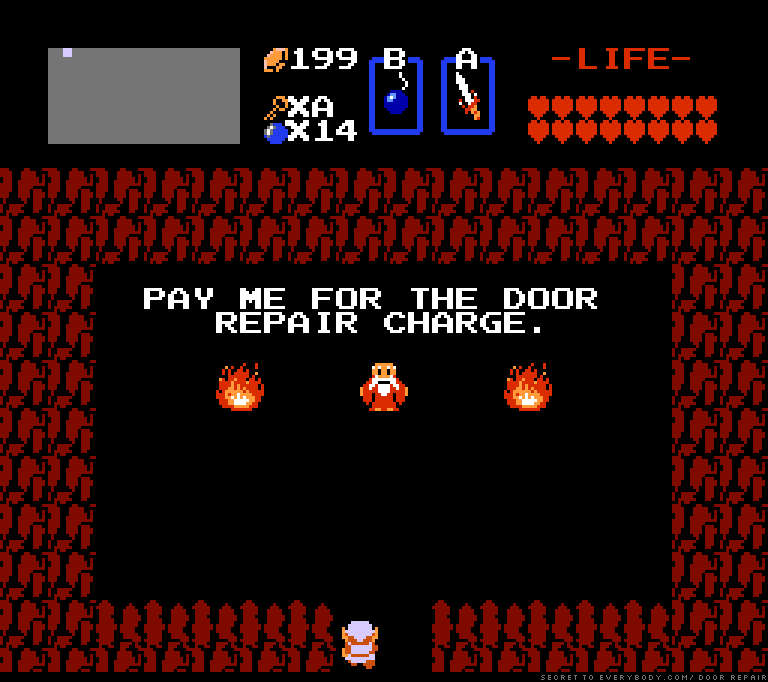

Several roadblocks kept Zelda from joining the U.S. launch. First, early NES games mostly used complicated passwords to save progress or simply forced players to start from the beginning every time they turned on the system. Second, Zelda heavily relied upon the FDS’s extra wavetable synthesis audio channel for music and sound effects so everything would have to be squeezed down from five channels into four. And finally, Zelda had substantially more text than most Nintendo titles at the time and all of it would have to be localized to English.

Rather than jump these hurdles right away, Nintendo focused on turning around a sequel in Japan for the FDS. Zelda II: The Adventure of Link released just under a year after the first game on January 14, 1987.

North American Zelda, Finally

The first Legend of Zelda would finally release on the NES on August 22, 1987. New battery backup technology allowed for simple game progress saves, composer Koji Kondo distilled more complicated musical tracks down to the NES’s capabilities, and the text made it through localization (with several bumps and bruises).

Zelda II wouldn’t release in the U.S. until December 1, 1988. It had to undergo all of the same types of changes as the first game and Nintendo took the extra time to improve and tweak the sequel as well. Everything from the leveling system to the palace/dungeon visuals to the game over screen and more was significantly altered.

While all of this is interesting in its own right, we will be focusing on select music tracks from both The Legend of Zelda and Zelda II: The Adventure of Link and looking at how the composers dealt with having to condense them down into a simplified audio arrangement.

“The standard NES, the [Ricoh] 2A03 chip has two squarewave channels, a triangle wave, a noise channel, and a sample channel. You don’t hear a lot of the sample channel. It’s in a few games but not heavily used because it takes up a lot of space. The Famicom Disk System has a fifth tonal channel, which is like a wavetable synthesizer almost. I’ve never got to really use it until now. Like, learning these songs, and I want to use it.”

— Thomas

The FDS included the Ricoh RP2C33 chip to incorporate the additional wavetable synthesis sound. Thomas has pulled the music from both the NES version and the Famicom Disk System into a program called FamiStudio (we used that program for the visualizations in this piece).

“FamiStudio is a program that you can use to compose music. It has a way that you can export these things visually, so people can actually see what’s going on channel to channel and get a good idea of what channel is playing what and how it’s happening. It’s a really good tool for visualizing these things that a lot of people might not fully grasp what they’re listening to.”

— Thomas

After taking some early listens to the tracks, Emily offers her initial thoughts:

“I think what’s important to remember is that the bones of the music remain almost virtually the same depending on which track we’re talking about. So for the most part, the structure of the music, the melody and the implied harmony, are there, and what gets ‘lost’ from moving from the Famicom Disk System with the extra audio channel to the NES is fluff. I guess it kind of epitomizes western music because this is western tonal music. It doesn’t matter that they wrote it in Japan, it’s like this was western harmony. And in those rules, you don’t need a lot of information to understand what’s happening harmonically. That’s why the NES, even though it’s pared down, you still get the main gist of everything that’s happening. It’s like having less icing on the cake, I guess.”

— Emily