Blog > Stories

Music Theory and Vintage Sound Chips: The Different Versions of Zelda’s Iconic Music

Blog > Stories

Music Theory and Vintage Sound Chips: The Different Versions of Zelda’s Iconic Music

Admiring Old-School Craftsmanship

Even though he composes his own modern-day NES music, Thomas Cipollone says working with these Zelda tracks was a learning experience. Playing around with the FDS wavetable synthesizer was especially enlightening.

“It’s very confusing, the wavetable stuff. When I look at how to set up those instruments, it’s like, ‘What am I looking at?’ That’s where I’m falling apart here. That’s what I need to learn. I need to dig into the internet and figure out what I’m doing wrong. I can’t make it sound like a whistle or a bell. That’s on me.”

–Thomas

“I didn’t know about the Famicom Disk System. I’d heard of it. But I didn’t really know what the deal was with it or anything. Hearing the richness of the sounds from that system, it’s been great. I’ve loved it. It was it was a real treat. Also, in fairness, it just solidifies to me how music doesn’t need to be epic and over the top. You can write really impactful, wonderful things with very few tools at your disposal. Modern music doesn’t have to be any different than that. Some of my favorite soundtracks of 2022 are some of the simplest soundtracks I heard.”

— Emily

Nintendo’s Famicom Disk System had a great run from 1986 to 1990, selling over 4.4 million units in Japan alone. Eventually, cartridge tech caught up to and surpassed the FDS’s early advantages. Battery backups allowed players to save progress, cart storage sizes surpassed disks, carts didn’t have to deal with the frequent loading and disk flipping, and retailers were happy to get the space-hogging disk rewriting machines out of their stores.

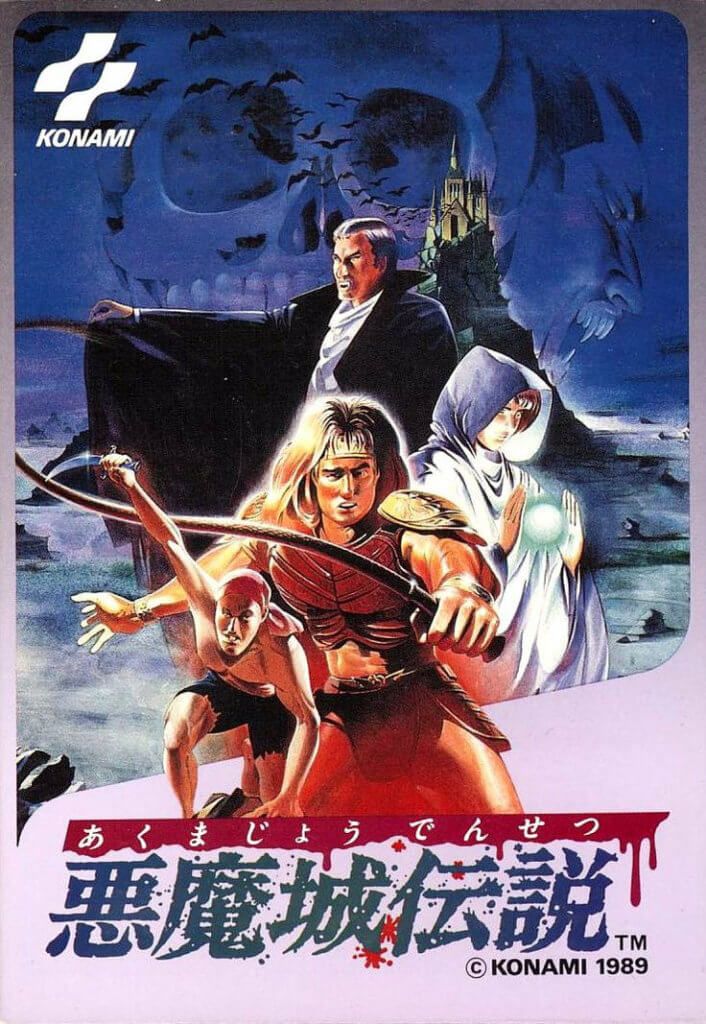

New Chips Offered More Sound Options

Once composers had a taste of the extra audio capabilities of the FDS, however, they found ways to enhance the sound of standard Famicom games by adding special chips. The most famous example is Konami’s VRC6 chip. It added two pulse waves and a sawtooth wave to the mix, nearly doubling the audio channels. The Famicom cart version of Castlevania III: Dracula’s Curse has an especially excellent soundtrack that pushes all of the audio channels to the limit. It must have been especially difficult to adapt that back to the limited NES, since the system was not built to support enhanced cart audio like the Famicom. Chiptune fans love to listen to VRC6 versions of their favorite NES tracks to imagine what it would have been like to hear this coming out of their 100-pound CRT TVs in the ‘80s.

Composing for the VRC6 remains popular in today’s chiptune circles, while the FDS remains obscure. The company Cipollone writes most of his music for, Retrotainment, manufactures their own NES and Famicom carts, but they have yet to attempt making Famicom disks. Not many people have them anymore, and the ones that are still around have a failure rate on par with, if not worse than, the front-loading NES.

“If there’s anybody that can figure it out, it’s the NES homebrew folks. If there’s something they want to do on the Nintendo, they’ll find a way.”

— Thomas

“You need those people in this world.”

— Emily

It’s been a whole lotta fun to dig into the audio tech behind one of the most cherished eras in gaming. Learning the extreme limitations composers had to work with at the time made my appreciation for their creativity grow that much more. Having the opportunity to add new dimensions to their sound with the extra audio channel on the Famicom Disk System must have been a dream come true at the time. On the flipside, scaling back their music after the fact to work on NES systems on the other side of the world had to be disheartening. They somehow made it work in the end and most western listeners never knew any better until the import scene developed and the internet grew out of its infancy. At least now we can appreciate these fresh, yet still retro, versions of the music tied to our most fond gaming memories.