Blog > Stories

Monroe as a Caesar, a Saint, a Copy, and Never a Person

Blog > Stories

Monroe as a Caesar, a Saint, a Copy, and Never a Person

Piety is Aspirational

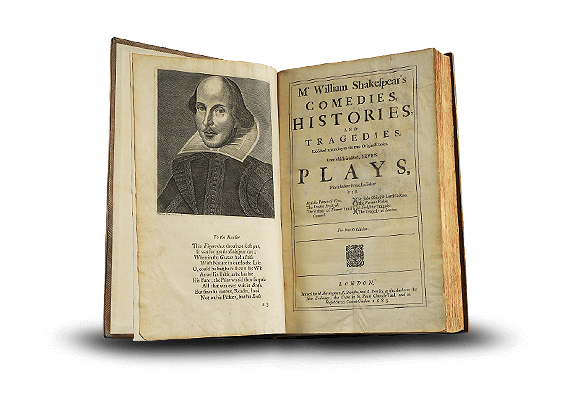

After the fall of the Roman empire, so much happened in the region, but one of the biggies was the rise of Christianity and its coalescence into the Next Big Patron. The Byzantine Empire existed from the split of Rome in 476 AD through the fifteenth century and the art associated with devotion and worship transitioned from the Roman’s reverence for wisdom* to the early Christian worship of, well, martyrdom**.

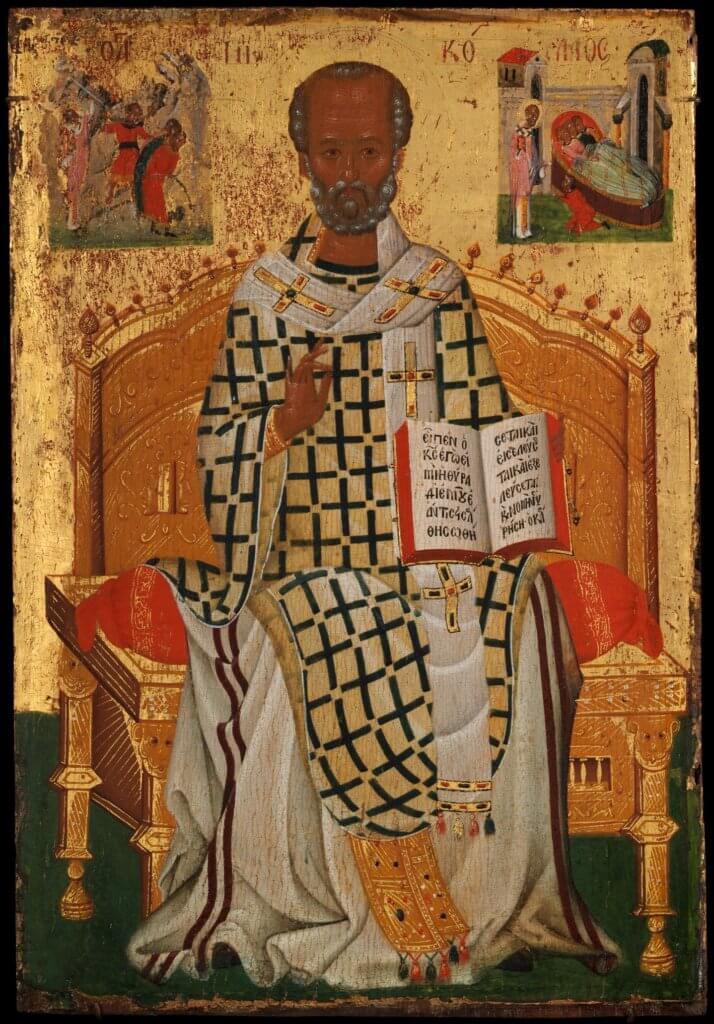

Instead of individualized, recognizable portrait busts, Byzantine artists and their patron, the church, maintained the repeated poses and emphasis on recognizability but made characters identifiable by traits instead of faces.

There was government-level concern about citizens conflating the entity shown in the icon art with the icon artwork itself, and the slippery slope towards the worshiping of false idols. Sarah Brooks says in the Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History that, “In Byzantine theology, the contemplation of icons allowed the viewer direct communication with the sacred figure(s) represented, and through icons an individual’s prayers were addressed directly to the petitioned saint or holy figure.”

There was government-level concern about citizens conflating the entity shown in the icon art with the icon artwork itself, and the slippery slope towards the worshiping of false idols.

A big part of this style was helpful for recognizability through repetition of idea symbols, instead of subtle human features that can be hard to execute by anyone other than highly-trained master artists. This isn’t to say that the Byzantine artists were no good, but that glyphs used to identify Christ could be sketched or ill-formed and still be recognizable. A doodle of one more old, white dude Caesar would be hard to revere with any kind of specificity.

The bottom right is Rally’s Justinian (1st Depiction of Christ on a Coin), 695AD and the others are from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Cheekbones were replaced with smoothed, egg-like faces divided by sharp straight noses. Backgrounds were often planes of gold leaf and their illusion of depth was flattened. Characters of saints and the holy trinity had consistent hand positions, props, or injuries for quick identifications. And all of them used these positions, symbols, and context clues to illustrate the idea of extraordinary holy purity.

And just like failing wish of longevity in Rome, who in the Byzantine Empire had the resources to be this pious? Who could ensure that they followed all the rules of the church when daily life was so freaking hard? Wisdom and purity are both so aspirational, so impossible to guarantee through your own individual actions, that they could be goals for normal people to think that the “chosen” elite have achieved. It’s a lot like fame, in that way.

- Note one*: This Roman wisdom didn’t always play out, but it’s what they told each other was important. We know

- Note two**: And yes, there were absolutely other traits being worshiped in early-ish Christianity, but the promotion of extreme self-sacrifice is frequent one