Blog > Stories

Monroe as a Caesar, a Saint, a Copy, and Never a Person

Blog > Stories

Monroe as a Caesar, a Saint, a Copy, and Never a Person

Artistic Repetition, Not Copies

Warhol knew all of this about the Caesars and the Christian portraiture, of course. Jennifer Dyer’s article includes a quote from Warhol. “Everything repeats itself. It’s amazing that everyone thinks that everything is new, but it’s all repeat.” And now we get to the criticism of quantity, of duplication, of studio assistants (or straight up makers). Was Warhol’s method a callous exploitation of the art market or part of the process? Is this even a Warhol-exclusive thing?

“Everything repeats itself. It’s amazing that everyone thinks that everything is new, but it’s all repeat.”

Andy Warhol

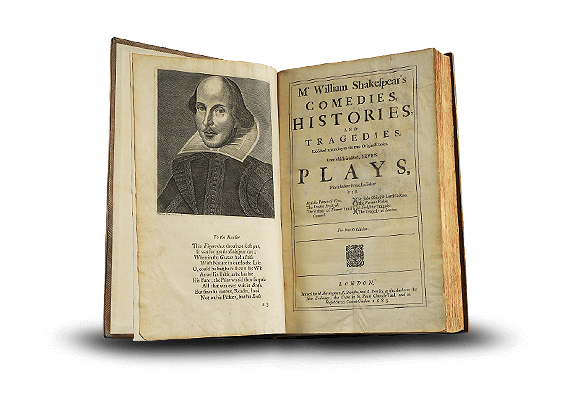

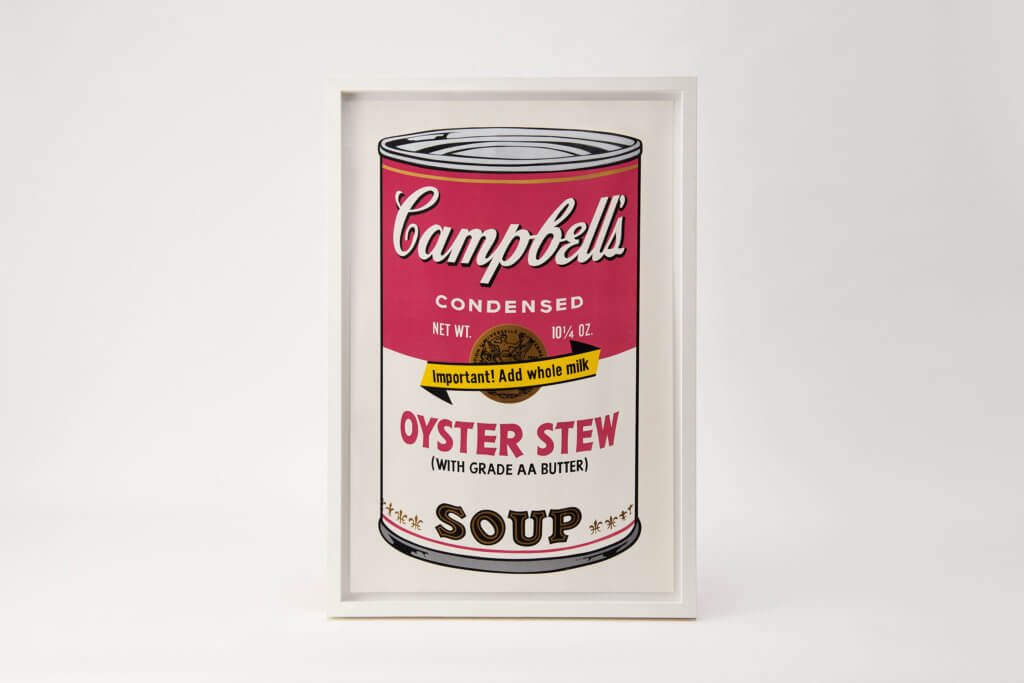

Warhol was raised Roman Catholic and worked in advertising for years. The blend of iconoclastic references from his religious youth with the ritual of “brand standards” from his time in advertising only duplicated the notion that an image, repeated, becomes a symbol and sheds its identity. Using soup cans and pop culture A-listers and manic colors, Warhol’s constant homages to capitalism, arguably the god of the 20th century, is both profitable and understandable.

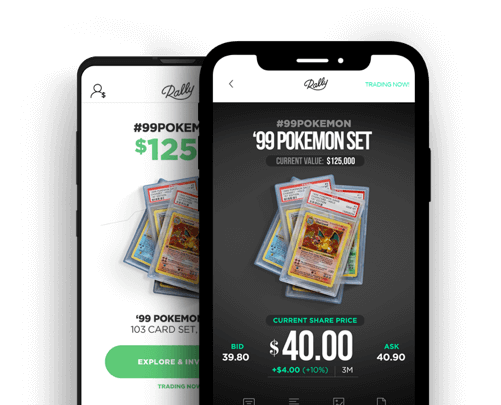

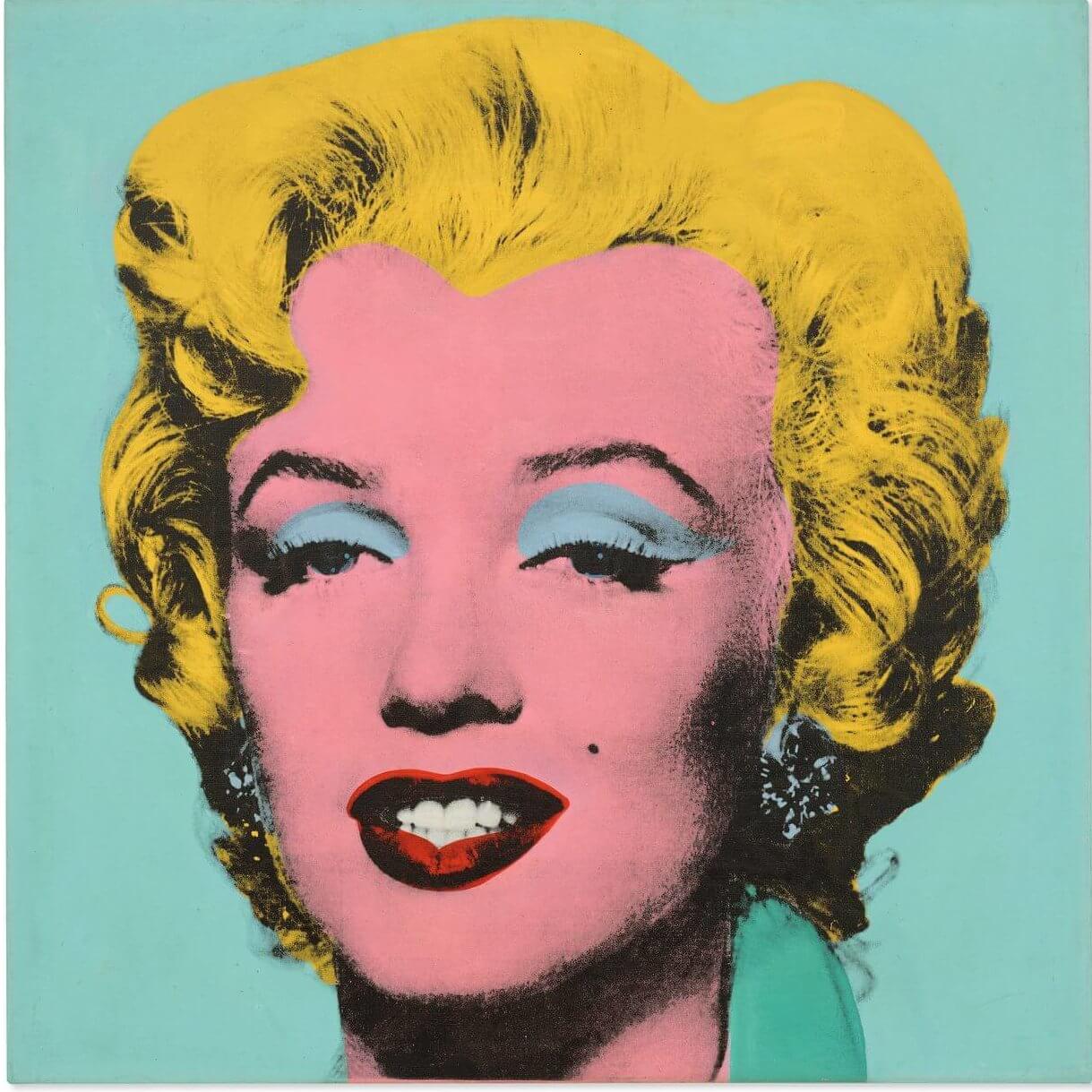

But where’s the line? Why does a series of 250, like the one that Rally’s is included in, have such extraordinary value when the main image is so readily available? What we see with the Marilyn portraits is a concept that’s used in a very specific balancing act – enough unique features to make scarcity, but ubiquitous enough to be instantly recognizable.

The souvenir versions of Warhol’s Marilyn portraits keep up the imagery that we’ve talked so much about. But the mass produced bags lose the series, the start and end of a meditative artistic attention.

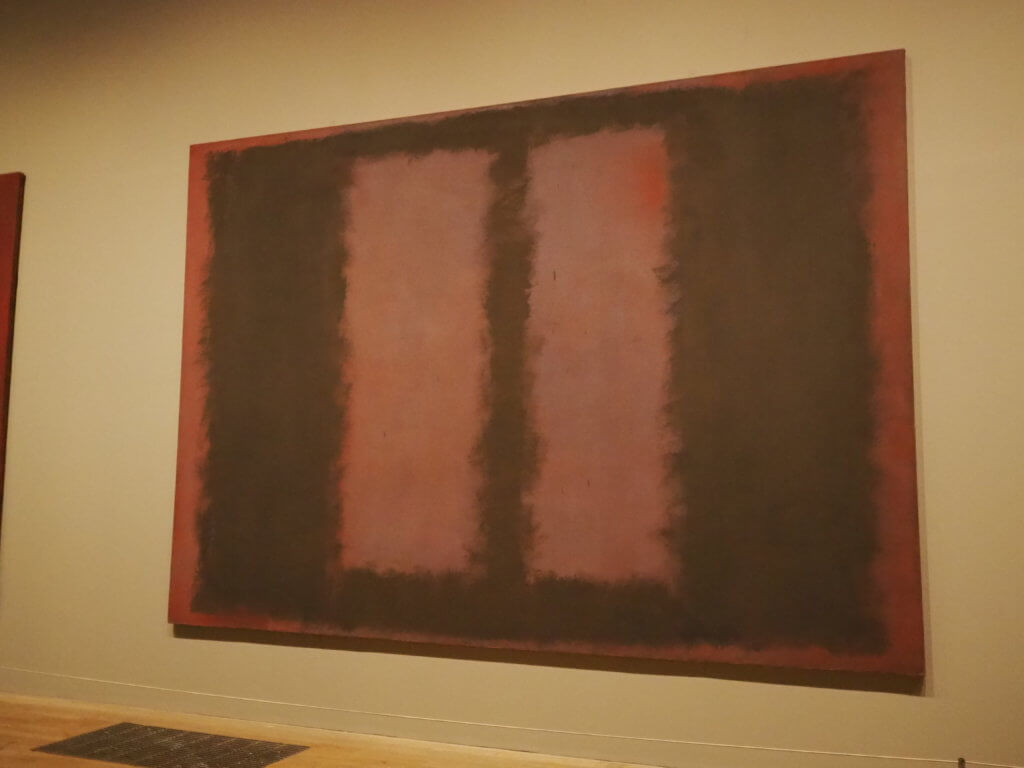

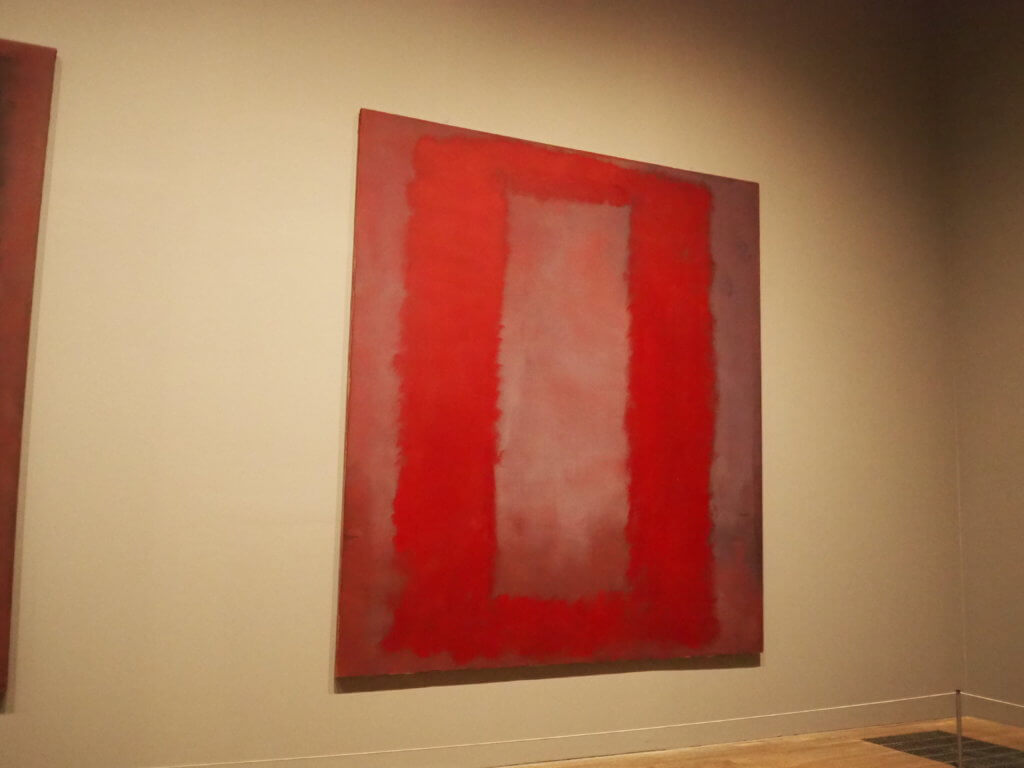

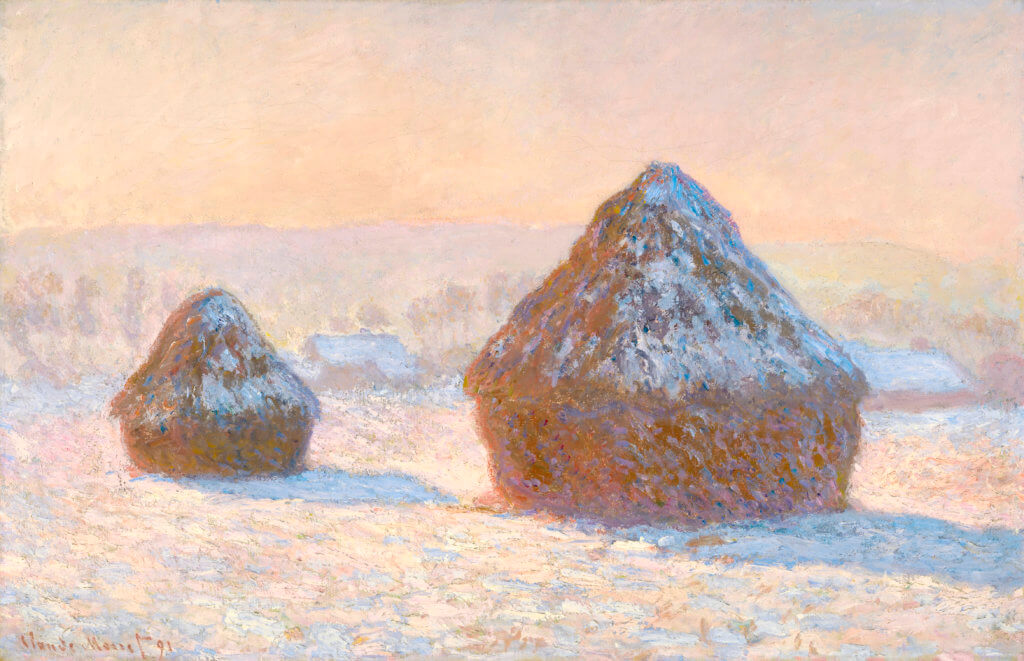

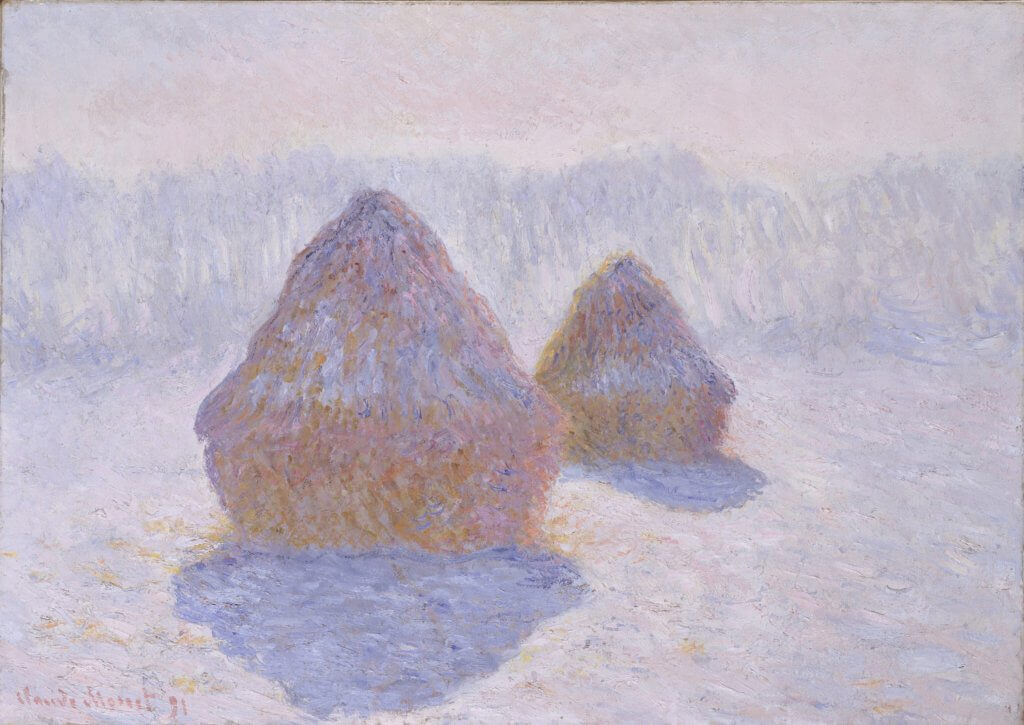

To Professor Elaine Gazada, criticizing a piece because it’s part of a series dismisses “… the advantages of repetition as a conscious artistic strategy…” And Monet’s haystacks comes up as a great corollary in Dryer’s article, when she loops in curator and artist John Coplans’ thoughts on Warhol’s use of repetition.

“However, time is an effect of serial repetition in Monet. … The viewer is led to read the passage of time into the shifting light of each image. … (John) Coplans argues that: Warhol takes the same image, repeats it, and creates in the viewer a strong sense of seeing a whole series of light changes by varying the quantity of black from image to image.”

Jennifer Dryer, “The Metaphysics of the Mundane: Understanding Andy Warhol’s Serial Imagery”

The handwork of a set of Warhol prints might not have taken a long time, although sometimes it did, but the handwork itself forces observers to consider a passage of time and a repeated consideration of the subject by the artist. It is a meditation and an observation.

And it was the same for Monet’s Haystacks and Rothko’s color fields and Degas’ ballerinas.

Bottom row (left to right): Haystacks, End of Summer by Claude Monet; Haystacks, Snow Effect, Morning by Claude Monet; Haystacks (Effect of Snow and Sun) by Claude Monet – images via Getty

So we should all just deal with it! Gazada says, “The act of classifying an object as a copy incorporates a fundamental denial of the validity of that object as a unique expression of its own time and culture.”